a closing with Lauren Sampson

NEWARK WITHHELD

Newark Withheld is a series by Sara Bissen about Newark, New Jersey today, as seen through the eyes of its long-standing artists.

Opened by Kevin Blythe Sampson, Newark Withheld initiates a discussion by local artists in relation to the transformation of their city. This series extends from the photographic work of Cesar Melgar in Newark,[1] featured in the rural issue of the Journal of Biourbanism.[2]

ARTISTS

Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.”

Gladys Barker Grauer—“Newark sensed it.”

Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.”

James Wilson—Newark, “when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home.”

German Pitre—“Newark has always been known for that edginess.”

—a closing with Lauren Sampson

This series closes with a review by the activist and artist Lauren Sampson, who is also Kevin Blythe Sampson’s daughter. Lauren graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Restoration of Art and Antiquities from the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City. She has worked for the Cardozo School of Law, Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, and the City Bar Fund at the New York City Bar Association. Much of her work has involved advancing social justice within the legal profession. Currently, Lauren’s work focuses on fundraising for exonerating the wrongly convicted and criminal justice reform at the Innocence Project in New York City. Her systemic view of Newark finds expression through her art.

SB: Lauren, given your direct experience with the artists included in this series—Kevin, Gladys, Cesar, James, Manuel, and German—I have two questions for you. First, what do they have in common, and how are they different from other artists on the Newark art scene? Second, what specific qualities do they have that make them important in understanding Newark, rather than other artists and other professions?

LS: In many ways, I am a child of the Newark arts community. My experience with the Newark art scene is a little different from others, because I grew up around it and then later became a part of it. All of the artists that have been interviewed have been a part of my world in some way or another for most of my life, and there are two words that come to mind when I think of them all: authentic and steadfast.

The Newark art scene has changed quite a lot over the last 10 years or so. More people moving to Newark from New York has begun changing the fabric of the art community. An art scene has been built on top of the existing one and has often excluded or has not figured out how to include those who’ve been a part of it all along. Newark is a hard city. In many ways it takes years when you’re an outsider to be considered a real Newarker. New people come in and think they understand Newark after a few months or years. It’s not that simple.

The people of Newark have a realness, a certain raw quality that gives the whole city a distinct flavor. Growing up here people often ask you what neighborhood you are from, because every neighborhood has a certain quality that makes it unique, but there is this commonality between them all and that is authenticity. I think what makes these artists’ work different from many others is that it is heavily influenced by the city and their neighborhoods.

These artists are all from different parts of Newark, but what they have in common is a sense of shared community. It doesn’t matter how the city changes around them, they endure. They don’t live on top of Newark, they live in it. They are Newark.

SB: How do you look at Newark and its relation to human creativity during times of decay or financial power?—especially now, as this impacts the body of the city with development plans, real estate investment, and gentrification.

LS: Newark has been in a state of decay for many years. I think that investment in the city and its infrastructure is great but not at the expense of its people and the arts community. They have lived through the city at its worst and deserve to still be a part of the community as it moves toward whatever vision the local government has for the city.

The thing that I find so disconcerting about rapid development and gentrification is when people start moving in and make it seem as if they’ve discovered some previously undiscovered land. What draws them in is Newark’s proximity to New York and affordable rents. Once they are here, they like “living on the edge” but not too much. Eventually businesses and developers start catering to the new population and the city’s identity starts to change, rent prices start to rise, and the very people that make up the soul of the city leave. In New Jersey, if you have a direct train to New York you are going to be taken over. They don’t care who’s been living there. They want what you have, and they will take it through purchasing power. Gentrification is not just an artist problem. It is a problem for all the current residents. As rents skyrocket everyone gets priced out. They try to dangle a carrot to artists and create artist housing that is affordable, but the rents are still expensive and a lot of the buildings don’t have space for the artists to create. They will have a “gallery” in the building, but what good is a gallery if there is no space to actually create work?

Even as Newark gentrifies, this will not crush the artists’ spirit or their need to create, and in some ways, it will embolden their work. What artists do is provide a voice for the voiceless. They speak for the people, and like many who come from less, they use art to transcend their circumstances.

SB: Can you speak about your artistic and social work and how it relates to Newark and its changes?

LS: Helping people is in my DNA. My grandfather was a prominent civil rights leader in New Jersey, and my father was a civil rights baby who fights for those in his community every day. I think every member of my family finds ways to fight for human rights in both their personal and professional lives. We have all been told since we were children that you can’t be for civil rights if you’re not for women’s, LGBTQ, immigrant, and all human rights. We should all stand together.

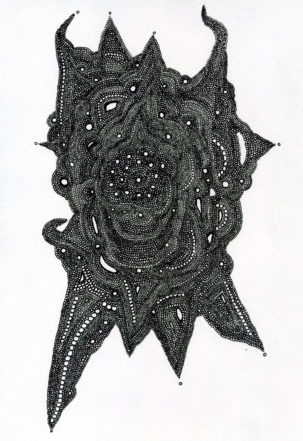

Though this family motto has affected what I do in my professional career—I work for a non-profit that exonerates the wrongly convicted and reforms the criminal justice system—it does not influence my art work as much as it influences my father Kevin Sampson’s. Where my father’s work pulls from his community in a more tangible way, my artwork is a bit more internal. I started my artwork to deal with my anxiety. I am deeply affected by what is going on in our country and what is going on in our cities, and I needed some way to channel what I have been internalizing.

SB: Knowing the recent changes that have been happening in Newark, what is the Newark you wish to see and live with in the future?

LS: As Newark moves forward, I really hope that the city doesn’t forget its people. The people that have been loyal and stayed through all the trials and tribulations. I hope that it does not continue to overlook its native artists and finds a way to retain their brilliance. Cities evolve, and populations change—but I hope most of all that Newark doesn’t lose its heart.

Footnotes:

[1] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 13-15.

[2] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark [All Issue Photography]. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015).

For further study, see: Newark—on Heterogenesis of Urban Decay