by Nilly R. Harag and Yamit Cohen-Liberman

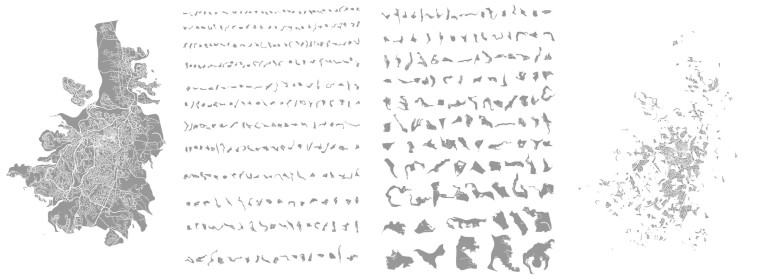

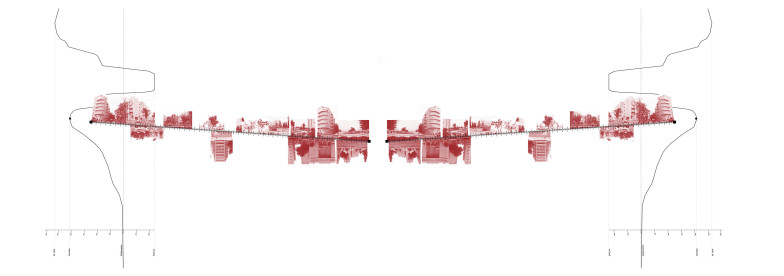

Arch. Nilly R. Harag and Arch. Yamit Cohen-Liberman from Bezalel Academy of Art & Design Jerusalem, presented an intriguing work on mapping during the conference MaPS – Mastering Public Space on last May. The conference was held at the MAXXI Museum in Rome by City Space Architecture with the patronage of the International Society of Biourbanism, and it brought together architects, urban planners and thinkers especially from the Mediterranean Basin. Harag and Cohen-Liberman inspired their colleagues about several subjects. It is their intuitions about cultural patterns that one can find again and again on different scales of the urban landscape that especially attracted me. A selection of urban settlements resembling an alphabet (fig. 1) is the most striking example. It unveils what is shown along the entire work, i.e. the symphony of human interactions beyond physical and geographical boundaries, with its own rules and rhythms.

We are thankful to the two Authors for offering their presentation for publication on biourbanism.org.

Stefano Serafini

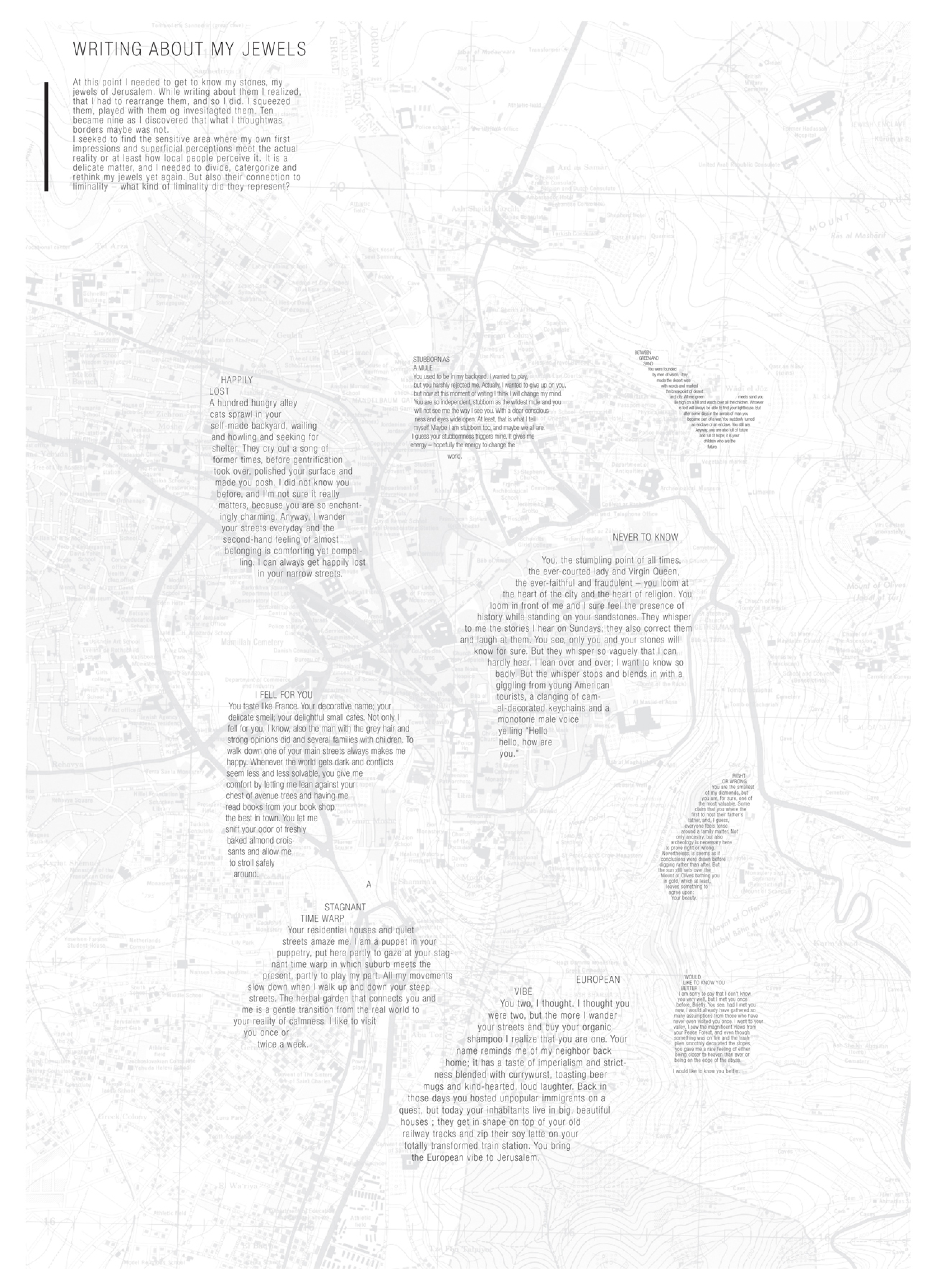

In 1654, the Carte de pays de Tendre was published by Madeleine de Scudery to portray tenderness of landscape by a female character in order to visualize a journey. This curious map visualizes the form of imagined landscapes in which the topos turns into emotions while making visible the invisible. Out of this the design grown out of an enormous journey. The exterior world conveys an interior landscape. Emotions materialized into topography. To figure out the land is to visit the personal and yet social psycho-geography, as Giuliana Bruno describes in her fascinating book (2002) Atlas of Emotions.

This was the theoretical gate to the world of mapping enabling the transformation of the world of mapping into an academic investigation while simultaneously being able to render the inner voyage into a personal cultural exploration.

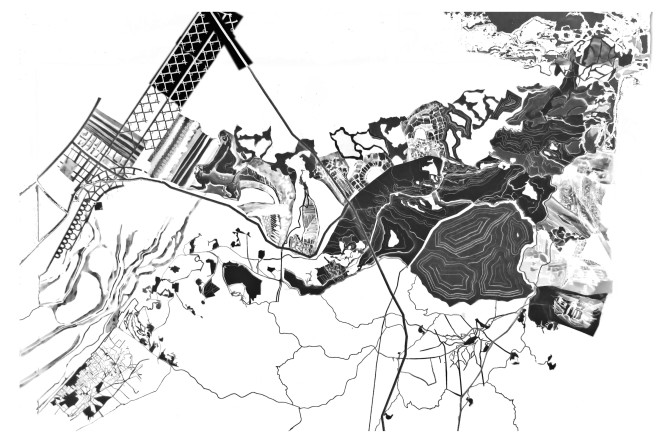

The art of mapping discussed in is not merely cartography. It portrays an autobiographical journey which transcends the real, the symbolic, and the imaginary and renders reality[1] into phantasmagoria.[2]

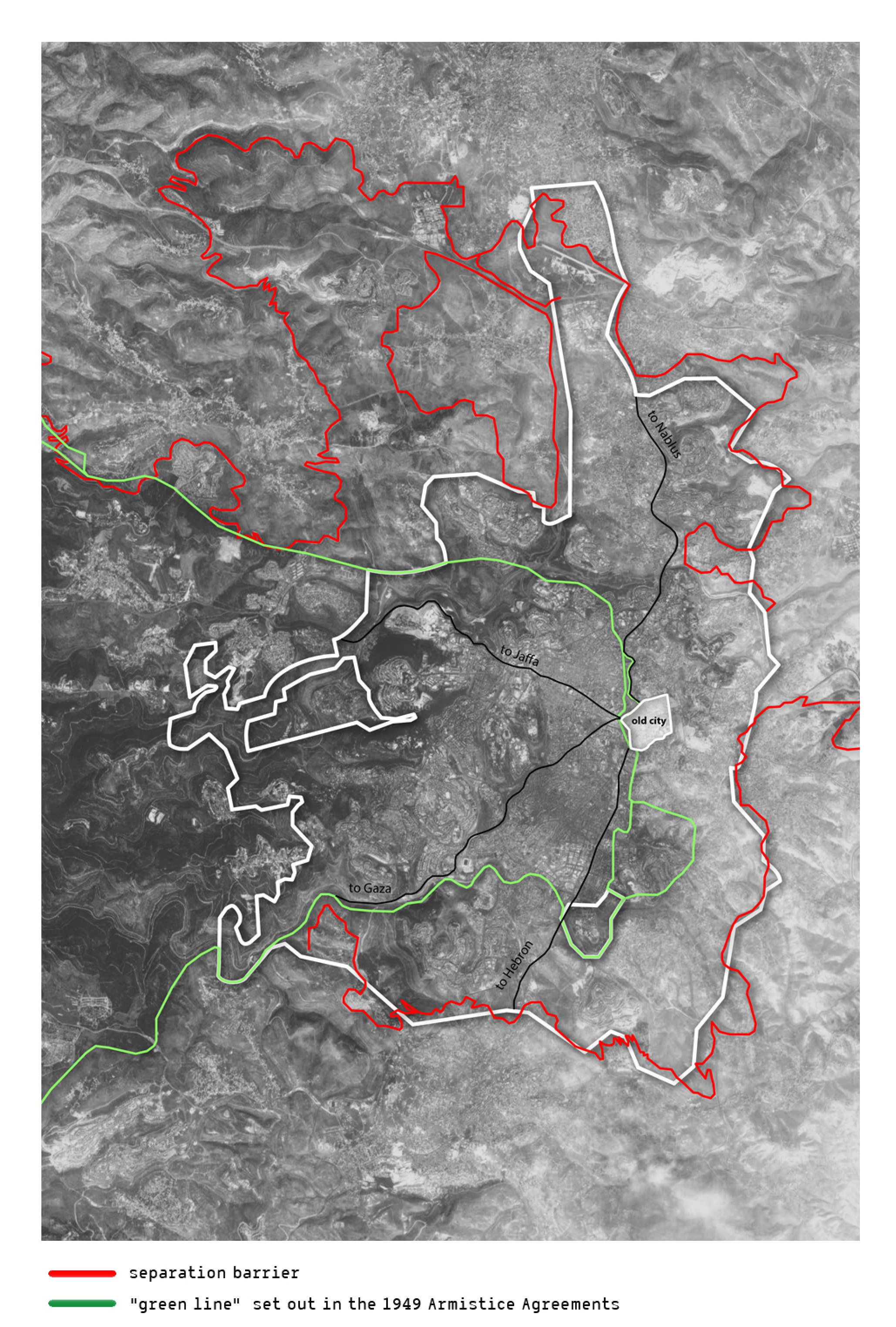

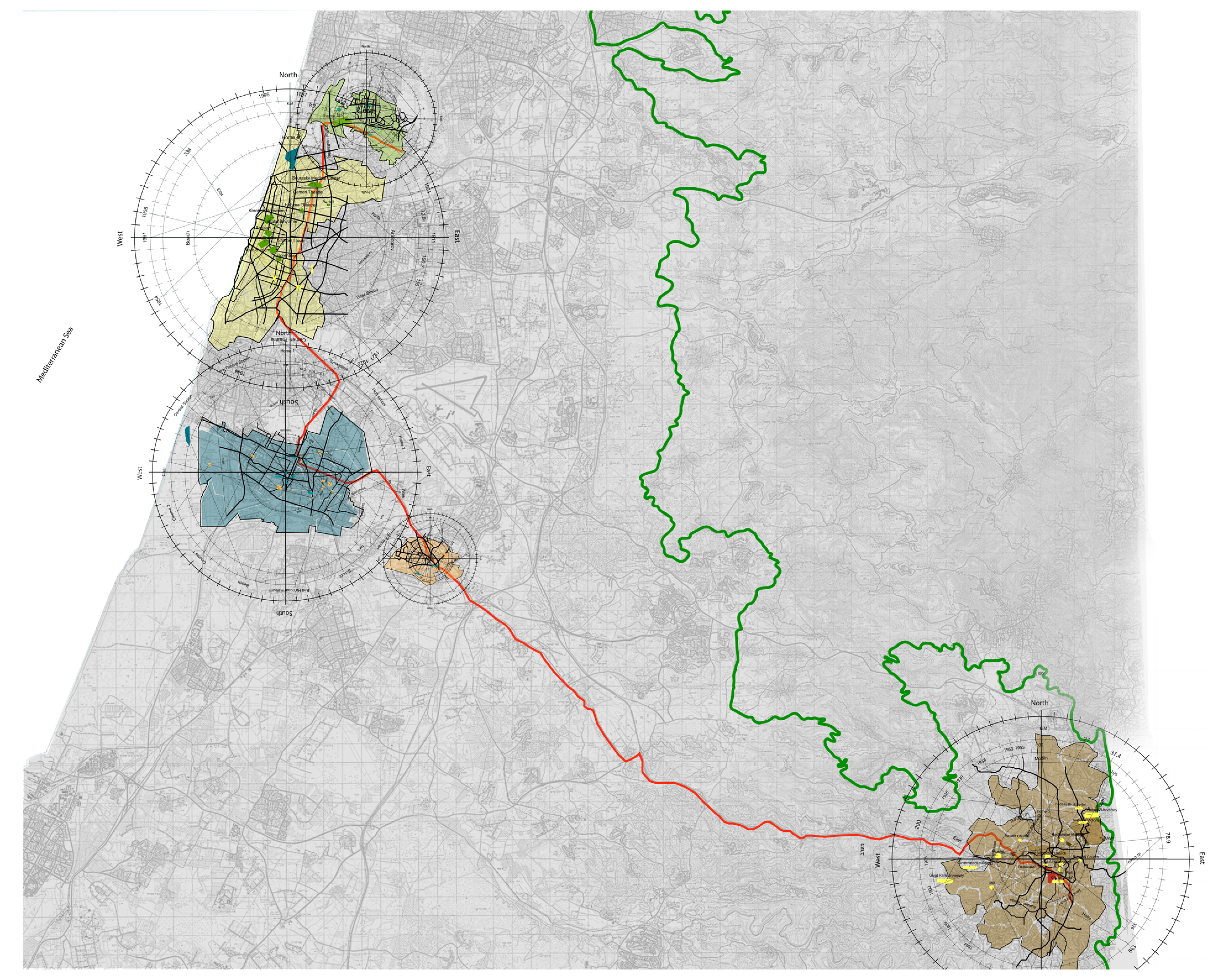

Take the projected map of the city of Jerusalem for example. It stands by the cartographic rules such as: legend, scale and topography but it contains an explosive narrative. We see mapping as a process based on site/insight approach.

Our notion of Mapping is an architectural and artistic investigation based upon cartography [but only] as a representational tool to create an “atlas of emotions” (in Giuliana Bruno’s terms) for a route we know rationally but have not mapped or documented via/through our personal experiences both as cultural pilgrims and political wanders.

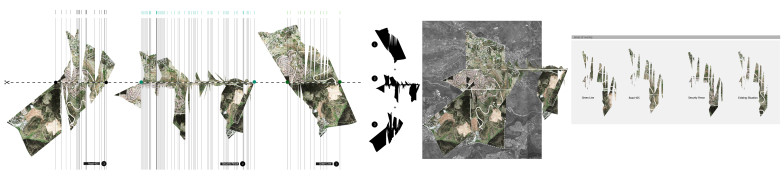

We may argue further that mapping is also an allocating mechanism. Along Wimsatt’s concrete universal, the act/art of mapping will provide a particular location where the architectural projection will be developed through spatial site investigations.

Once the site is discovered/allocated, the edifice is miraculously found.

Mapping redefines exhausted narratives and offer new ways of grappling with primal human question-be it in architectural, political, artistic and environmental arenas. The approach seeks to relocate the human empathic gaze as the locus of architectural praxis.

In line with Lacan’s notion of the symbolic language, map-making is never a single consistent mode. The symbolic, the imaginary and the real can be used as orders to interpret the world. This enables us to look at the action of mapping as a process that bridges the symbolic and the imaginary. This bridge is constructed atop the real.

Let me further explain how these notions of the symbolic language relate to the process of mapping in our eyes.

Reality is made up of images. These images are made up of symbols. A symbol can represent the presence or the absence of something. A symbol’s meaning is derived from the relationship it has with other symbols.

The real is everything that falls off the grid of symbols. It is what is built and cast. It is what you encounter and cannot symbolize.

The imaginary thrives in-between the real and the symbolic and is the field of images and imagination as well as deception. It is based on identity, the ego and the self. We can consider it as a reflection of the self that grows out of the unconscious.

The process of creating a map, as an imaginary document constructed out of symbols, is never a single consistent operation. It is a process of reduction. We begin by assessing the real, the world outside. We then use symbols to describe our observations. We symbolize what we see and what is missing. We do this by applying the imagination, which is our subjective representation of the real. The imaginary is the range of apprehensions manifested by the self through subjective perceptions of the real and the symbolic.

This is influenced by autobiographical aspects of the self.

We relate this process of reduction to a fundamental idea found in the history of religion: ”Man is a micro cosmos and the world is a macro-anthropos and what is in one is in the other.”

This is the notion of a man-cosmos link, i.e. , cosmos being an ‘enlarged humanity’ and vice versa, man being a ‘small version of cosmos’. It is an example of the properties of the reduction process. We contain a subjective representation of the real in an object, while still preserving its original characteristics.

We see the map as a concise world. The concise world is created by man, who is the in fact, the wider essence of the world.

In this process there is great influence of autobiographical aspects. The creator of the map adds, deletes and overlooks different properties according to his own perception. This is why the idea that maps represent an objective view is incorrect.

When we analyze the autobiographical aspects, we realize the presence of the subconscious, which sees both frameworks simultaneously. The first framework is the symbolic language and the second is the notion of reduction. We realize that the making entails to be in-between even as subjects. Confronting inconsistency, we discover an authentic hidden identity that manipulates space inside out. So, authenticity is not a matter of corresponding a sign to reality, but rather it is the failure of the sign to correspond to reality, which, in the process of failing, reveals the real. What is revealed is a personal reality from which we can and should deduce on the general reality and the concrete universe.

The process of forgetfulness is a more dynamic incentive than the fixed memory we carry within us. The use of short-term memory incorporates meaning as an active tool with the capacity to sustain identity. The objective history is too bored to be read. That’s why we need the historical novels or narratives to project our ideas. The context in which those narratives are invented aimed at carrying forward the memory of an event; even of a conflict, even if does not necessary really happened. It is a well-known phenomenon that we need to reshape the past in order to let our culture survive.

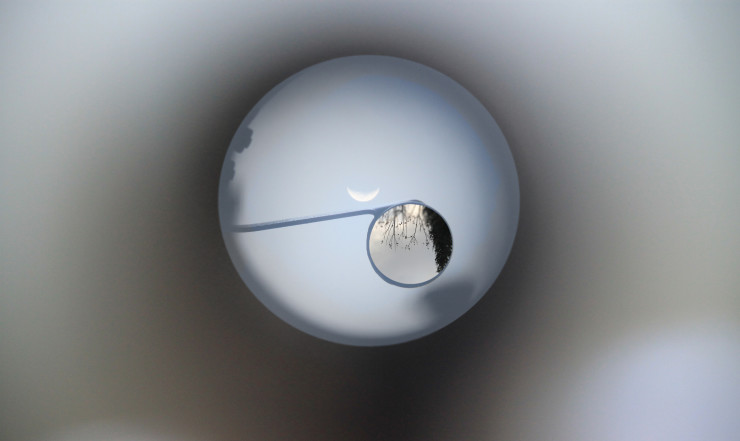

Sometimes one has to forget, to suspend the meaning of long-term memory in order to be able to see but not be drawn into reality. Departing from painful memories can provide the capacity to contain that memory but, at the same time, to continue one’s own way towards a new beginning. Thus, the art of mapping is introduced as a lens which can constrain the scope of the event, change it or even enabling the invention of the fictional parallel to reality. The objective truth resides only in the creators’ artistic mental capacity.

Creation based on the use of the past is a strategy most cultures use in order to provide stability. We tend to believe that we are linked to those who have preceded us. We have ‘roots,’ as we often say. These roots give us stability and direction, and most cultures seem to revert to their roots. The problem originates when we fail to understand that we do, in fact, create the past as a product of our present needs.

The driving tool for making maps is based on the shift between phantasm and reality, which creates a liminal space perceived as the concept of uncanny.

While place is a piece of territory shown we aim to question its boundaries shown on maps. The observations are the cultural trigger to question our spaces. Our place is never caught naked in itself it is always part of the bigger space.

The Art of mapping produces a broad cultural debate while possessing the ability to introduce new practices into the architectural debate.

In order to be able to discover something new we have to go back to the same roads we took before but surly every visit will reveal something new inside us. Sometimes as did Saint Augustine or in the idea of the Phantasmagoria [which was a form of theatre which used a modified magic lantern to project images onto walls, smoke, or semi-transparent screens, frequently using rear projection. The projector was mobile, allowing the projected image to move and change size on the screen, and multiple projecting devices allowed for quick switching of different images.] Indicating we do not have to take an actual travel we can do it in our minds while reading maps.

The driving tool for making maps is based on the shift between phantasm and reality, which creates a liminal space perceived as the concept of uncanny.

Notes

[1] Pedaya, Haviva; Expenses: an Essay on the Theological and Political Unconscious” Chapter 1 “Spaces: Real, Symbolic, Imaginary and Reality pp. 21-28

[2] Phantasm: “An apparition or specter; a creation of the imagination or fancy; fantasy; A mental image or representation of a real object. An illusory likeness of something.”

Images by the following students at Bezalel Academy of Art & Design, Jerusalem: a. Elad Yahna; b. Inbal Omer; c. Alex Topaz; d. Kosta Geysman; e. Tai Pinchevsky; f. Trina Gaard; g. Coral Hamo; h. Ida Hojlund; i. Amit Rivlin; j. Keren-Christina Mendjul.