by Sara Bissen

German Pitre, Newark (June 2018). Photograph by Cesar Melgar.

NEWARK WITHHELD

Newark Withheld is a series by Sara Bissen about Newark, New Jersey today, as seen through the eyes of its long-standing artists.

Opened by Kevin Blythe Sampson, Newark Withheld initiates a discussion by local artists in relation to the transformation of their city. This series extends from the photographic work of Cesar Melgar in Newark,[1] featured in the rural issue of the Journal of Biourbanism.[2]

ARTISTS

Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.”

Gladys Barker Grauer—“Newark sensed it.”

Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.”

James Wilson—Newark, “when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home.”

German Pitre—“Newark has always been known for that edginess.”

—a closing with Lauren Sampson

Interview (December 30, 2017) with German Pitre by Sara Bissen

A phantom city floats against the skin of a society to suck value and purpose from its flesh. It renames identity. Artist German Pitre sees it and creates art while facing this apparent magic that produces money from “nowhere” in a financially-driven city such as Newark.

In fact, Pitre has noticed a silently violent “counter” body of the real Newark that appears rational but moves as a marionette. He has been making art for over 35 years while critiquing the ways in which domination and oppression have manifested into what he refers to as a corporation. These systemic paths make or get something from nothing.

The Artist is currently facing displacement at 31 Central in Newark and places his work within the irrational machine of our system. Pitre talks about the artificial processes of a rationally blind system that pretends to drive real value. Even finding humor in this “counter” body’s logic—especially in how its appearance differs from the inside—Pitre has identified a logic that takes from the equation.

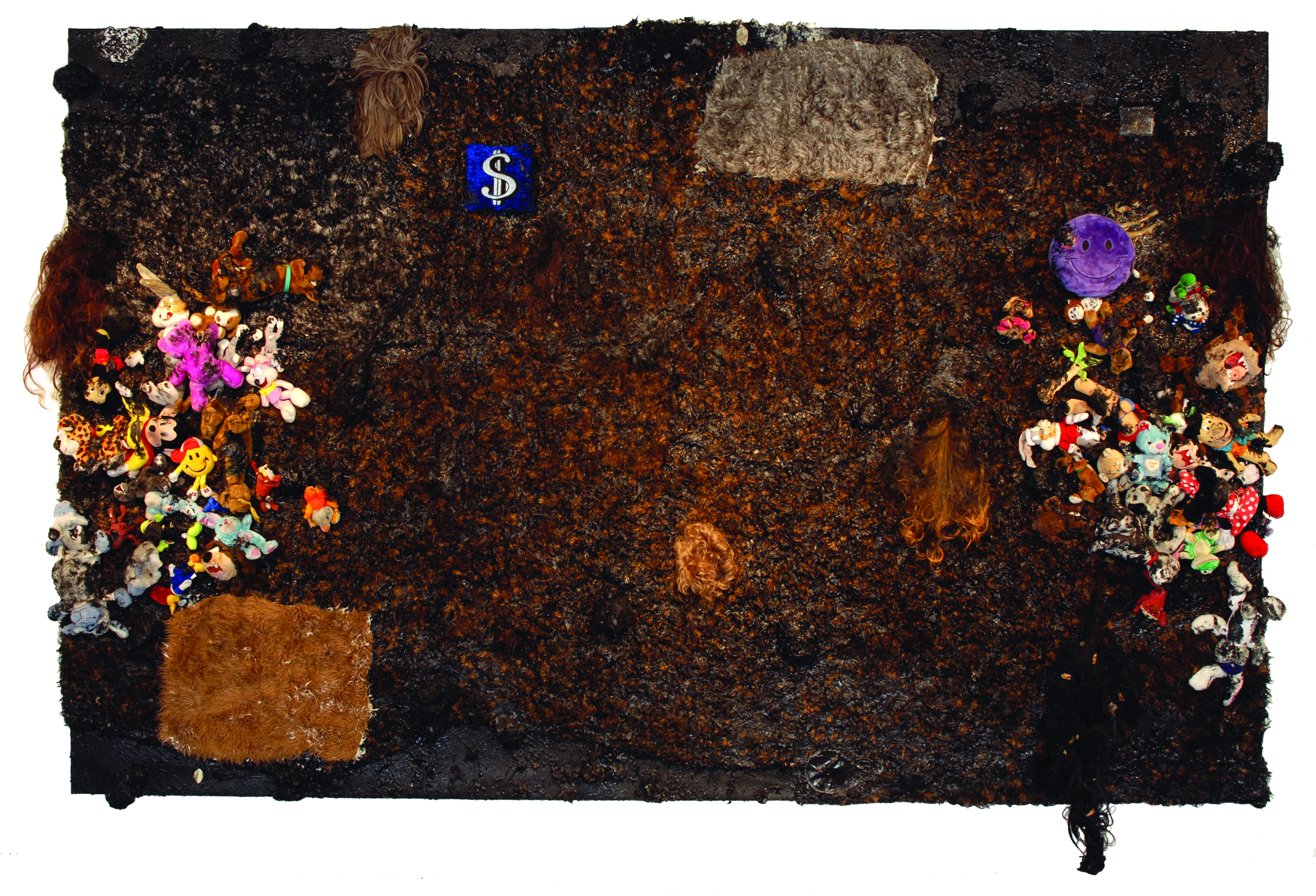

Any Fate But Surrender (2017) by German Pitre. Mixed media, 96 x 150 x 5in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

7 Lincoln Heads (2017) by German Pitre. Casting wax. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Wolf. Imperial Empire Dreams of World Domination and Power, Oppression, Corporate Shareholders and State Interests are the titles and themes of his works. They are materico paintings that resemble sculpture made of childhood objects and familiar icons. Through the universal identification of stuffed toys, Pitre shows an implosion that takes life away from itself in order to eat itself. The innocence, passivity, and commonality of the plush animals expose a dark and total reality. This darkness has mutated into a consumeristic destruction that has gone beyond all forms of past powers.[3] In the end, the stuffed toy is liquified to make it look like the toxic surroundings that it has ingested.[4]

Accumulation and Ecstasy and Mercenary Empire are Pitre’s close-up photography of this whole yet mutilated swallowing. Within the debris, Pitre is resourceful in finding the materials he needs to create his art. Therefore, in one sense Pitre makes art from nothing like the phantasmic system of value we live in. Yet Pitre’s “nothing” has substance and the fact that he can work with few resources questions the financial business of “art” and how it produces money from a phantasmic nothingness.

Pitre stresses the importance of making art. People can change masks easily but relevancy is not transferable. Pitre, as other artists of Newark who are moving a reality, looks into the future, and with his art feeds his reality by saving it from eating itself while the phantom of financial art seeps into Newark bringing the nothingness of capitalist value.

SB: Can you talk about the social and political dynamics of your work?

GP: In the beginning, I had misnomers about identity. What I mean by identity is being black. I later found this to be rather a social, political designation. I started to realize that, we, these people who think they are African American, could not be. There are no such people as African Americans that tie back to any nation because black is an adjective and not a proper noun or a noun. I then had a better understanding of identity and could see things clearer politically.

SB: And how does this relate your art to Newark?

GP: Newark is undergoing redevelopment, that is, gentrification. The real estate and cost of living has displaced many families who have spent most of their lives adversely affected by a lack of city services, mismanagement, crime, and slum landlords. My works are definitely a protest and reflection of these various ongoing problems (mass displacement is only one of them) resulting in homelessness, broken families, addiction, undue assaults, unlawful arrests, and domestic abuse.

Reichstag 9-11 (2016) by German Pitre. Mixed media on canvas, 96 x 120in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

In my community, I have seen the heavy hands of the U.S. and its pretenses. This is very important to me because work is not decoration. Newark, you know, has come out. Now, Newark is going through this “renaissance”—the moving of the people who dealt with all the grief. Part of this gentrification is the prison industrial complex. This also plays a role because if you can get enough people out of the community, they are locked up. By the time they get back they are no longer able to come back to the apartment or they have lost their homes, for those who did have homes. They tax you out if you have a home, so it is not just one thing.

That is why I use plush toys in my work. It has seemed like a segue into some of those social, economic, and political issues that the African American and the so-called black community has to deal with, between Newark and my paintings.

Deablo. Venture Capital and the Deconstruction of Free Will (2008) by German Pitre. Mixed media on canvas, 108 x 168in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

SB: Do you think Newark was de-industrialized to make room for a new market?

GP: A lot of buildings were taken down because there was a certain group of people that wanted everything and another group to have nothing and to be subservient and accept it. There is subjugation. They took down a lot of buildings for offices downtown, then, after no one paid attention to them, also outside downtown. A building might have burnt, so they took it down and did prefab… basically, I think the people who were taking the buildings down were just people with bad taste.

This goes for housing, warehousing, and creating fewer properties. Put the word “luxury” in front of housing and that is a code word for: ‘If you don’t make this kind of money then you are not welcome’. But if you have this, then you can come in. There are certain groups that have more access so they are able to afford those spots.

The thing about Newark and de-industrializing is that it happened. This is what happens with the industry and things being produced. It is almost as if there are too many people now and not much for them to do. Anything extra is to justify the extraction of some kind of finance from you.

SB: Why are the titles of your work important?

GP: Title selection plays a big role in the creative process. Democracy Through the Barrel of a Gun, No Boo Boo, Deablo, and It’s Assimilation and Annihilation. These works visually express the conditions plaguing oppressed people worldwide.

Allodial Supreme, Plug and Play (2017) by German Pitre. Mixed media, 56 x 80in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

SB: It seems you are not seeking to allure viewers through easy aesthetics. What happens between your artwork and the viewer?

GP: After viewing my art, viewers express mixed reactions. Many would laugh because they see the humor in the work. However, some have confessed that it seems dark and scary. Then there are those who have really liked the work. I have gotten it across the board, but I have never gotten indifference. As for me, I have always been interested in having a dialogue about the work and why it exists.

Visually, I want it simple. Conceptually, I want it to be very difficult work with many layers. When I say layers, what I mean is the way one can look at it today and maybe a month from now or a year from now. They see something different. I want to create works that are relevant. That is the way I produce work, so it cannot be easy. Relevancy is very important, in Newark as elsewhere. Artwork, like music, should talk about the time you are in and the possibilities of tomorrow.

SB: Has your art changed over time?

GP: Yes it has. For example, at a certain point, I introduced familiar symbols such as skulls and crossbones. Yet the underlying theme of oppression = greed + corruption has remained the same.

I initially had limited resources so paint and canvas were sometimes unattainable. Most of my picture frames are custom-built, even their folding frames. Since 1977, I have been creating works using toys stapled to boards. I painted by mixing toys with other materials. Most people have cherished plush toys as gifts or side objects. They have a common background. What I was thinking about and looking for were icons or objects that people could relate to easily.

Protect the Noun Interceptor Destroyer (2017) by German Pitre. Mixed media on canvas, 36 x 48in.

SB: How do you support the freedom of your art?

GP: I support the freedom as an art installation vendor contracted by various not-for-profit organizations.

SB: What makes an artist native to Newark?

GP: To be native to Newark is to be more than just a “resident”. I was not born in Newark, but I was raised in Newark. I, like many other grassroots, advocate for issues and vote in Newark. Relocating to a place does not make one native.

Newark has always been known for that edginess. It is a very creative place. Being a Newarker basically came about because of gentrification.

I came here when my parents were migrant workers. We started in the South and would go up to Buffalo, New York. We would travel with the season, picking string beans and tomatoes. We would travel back down South, so my mother stopped off here in Newark. I grew up in the projects, basically Baxter Terrace. I would hang at Columbus Homes because of schoolmates who lived there. If you did not know anyone, you did not go to certain neighborhoods. If you knew someone, then you got a pass. That was growing up. Then a time came when people who had never dealt with the grief came in and most of them were artists.

That changed the look of Newark and that is where we are today. Before you know it, things will change. It is going to look totally different. This gentrification that is happening in Harlem and most of the cities around the United States looks as if it is natural or organic. It really is not. Lots of money has been pumped into Newark that came out of, and I will use this word loosely—nowhere. It is coming from somewhere. From these cities, they could not find money from “nothing”. That is why there was this issue about who is a real Newark artist and who is not. At the end of the day, it is like an identity theft.

SB: What is the body of a city—as flesh, life, or life force?

GP: The people are the body of a city. The life force is the collaborative movement and aspiration towards a greater good for all.

We are going through an undefined transition right now. The newly arrived artist is like the canary in the mine. They send artists out into these rough areas to clear the land because they do not wear suits and seem a little rough around the edges. People in those communities do not pay that much attention to them. They bring their way in. I think this explains the body and the artist community.

When I hear people talk about artist issues such as housing, those are human issues that everyone deals with. It is not particular to artists. So, as artists, why do they not join up with other people to bring the body together and make a movement? They never do. Rather, they isolate themselves because they want to be elite. The body does not meet up. Even though the issues are the same.

This is a social responsibility and a human response to conditions, here and in the world. There are individual needs that people have. But who calls it out? There has to be a new base to adapt to the way things are being done today.

SB: How is this related to the bodies you use in your painting?

GP: The plush toys, symbols, and other attached objects are the focal points. The viewer is the body that completes the process.

Capitalist Tool You See the Trouble With Me (2008) Mixed media 64 x 78in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

SB: Why do you make art?

GP: I have always felt the need to make art! Throughout the years, I have realized art enables me to express ideas, concepts, and experiences that engage my audience in dialogue.

SB: How do you think art will change in Newark?

GP: I cannot say aesthetically; this is all speculation. They may have more galleries. In the future, I do not see Newark being comparable to “first or second tier” galleries in New York. Newark has always been on the verge of coming up and becoming a major player. The only problem: Newark is in close proximity to New York.

There was a time when Newark was known for having those hard-hitting artists. They might not have become known in all the major galleries, but they were very edgy artists. That is the whole thing about that Newark label.

SB: Do you think your work represents the irrationality of our system?

GP: Yes and no. I am not part of the irrationality that has been forced on me or my community. Art is not regulated and serves itself. It follows an order even within irrationality. You need to understand the machine. It complicates itself and is very convoluted. On appearance, it looks one way but moves a different way.

SB: In which ways, do you think, personal freedom is trapped in Newark today?

GP: I cannot speak for others personal freedom. I am dedicated to the art and I am going to keep making work. But as an artist, when you push through, you are going to see something that you are not going to like. That is the scary part. Most people spend their whole life and never push through the brick wall or veil that artists often have. They will be fine with that. If they can eat from just being where they are, then they are going to stay there. But in the long run, the writing, the work, or the building will ultimately be irrelevant because they did not push through to meet that other place.

Exhibiting for over 30 years, Pitre’s selected solo exhibitions include the Jersey City Museum, Jersey City, New Jersey as well as Rupert Ravens and City Without Walls, both of Newark. Pitre is a 2007 Joan Mitchell Foundation grant recipient. For more on German Pitre, see Contra Disambiguation at Rupert Ravens Contempo with commentary by James Kalm, featuring Pitre’s “Deablo Venture Capital and the Deconstruction of Free Will”. The Artist’s paintings and photography can be found at germanpitre.com.

Footnotes:

[1] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 13−15.

[2] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark [All Issue Photography]. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015).

[3] Pasolini, P. P. (1975). Il genocidio. In Scritti corsari [Corsair writings] (pp. 226−231). Milano: Garzanti.

[4] Bauman, Z. (2000). Time/Space: Emic places, phagic places, non-places, empty spaces. In Liquid society (p. 101). Cambridge: Polity Press.

For further study, see: Newark—on Heterogenesis of Urban Decay