by Sara Bissen

Manuel Acevedo, Newark. (2002). Self-Portrait from Night Projections. Gelatin-silver print, 11 x 14in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

NEWARK WITHHELD

Newark Withheld is a series by Sara Bissen about Newark, New Jersey today, as seen through the eyes of its long-standing artists.

Opened by Kevin Blythe Sampson, Newark Withheld initiates a discussion by local artists in relation to the transformation of their city. This series extends from the photographic work of Cesar Melgar in Newark,[1] featured in the rural issue of the Journal of Biourbanism.[2]

ARTISTS

Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.”

Gladys Barker Grauer—“Newark sensed it.”

Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.”

James Wilson—Newark, “when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home.”

Manuel Acevedo—“In Newark, I can imagine a new building but in decay. The way I see it, the completion is relative.”

German Pitre—“Newark has always been known for that edginess.”

—a closing with Lauren Sampson

Interview (March 14, 2017) with Manuel Acevedo by Sara Bissen

Manuel Acevedo does not tell what he has been told. He does, however, tell what he has internalized. What he has taken in, over time, has been Newark—as defined by his place in it.

Shedding light into a place, as Acevedo does, beginning from Newark’s West Ward as the origin of his work, is not for the purpose of surveillance or the kind of sight that modernity has instilled in us. Rather, by presenting unformulated options, visualizations with social commentary, and derelict landscapes with more than one point of view, Acevedo unflattens a one-dimensional perspective.

Backseat from The Wards of Newark (1982−87) by Manuel Acevedo. Inkjet print, 11 x 17in. Gelatin-silver prints 11 x 14in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Seeing is a way of creating at the same time reality and ourselves. Acevedo refers to this as a territorial imperative—a perception and way of thinking that has social, physical, and political implications within one’s own environment. Between fiction and non-fiction, Acevedo’s artistic attention moves from people to landscape in a perpetually changing city. Yet there are times when reality becomes unreality—reality being life, and unreality a materialized takeover that is the subsumption of life in a form of wasteful consumption.

Questioned about the uprisings experienced along the history of Newark, he says that they were the last possibility for communities to react to the condition of imperialistic oppression. That’s about the past. Acevedo says that Newark is now in a “state of limbo.” This may mean, perhaps, that Acevedo is in a state of limbo. Such a situation is, according to him, a residual that hinges on a point. This point asks for the truth of something we may not outwardly know. From Acevedo’s perspective, not knowing can rest upon whether or not a structure is being built or taken down, a project completed or left unfinished, or a story told as myth or reality. It is from this point where Acevedo’s sight brings a particular understanding of Newark to the surface, from the worldview of a limbo inhabitant. In what is known to him, this perspective is of an unknown being found in the states between. And this happens, as described by the Artist, in the real place of the five Wards of Newark. Calling them more than a city, Acevedo determines the different internal perspective that the Wards shed on the whole of Newark.

The symbolic character of capital has begun to show itself in Newark, and Cesar Melgar has shown it. He has exposed the profit behind design that became a consumption of reality.[3] The thought behind design has materialized into an unreality. There are times we can see this and times we cannot. Melgar, in Razing History, states that “Newark is only in purgatory from a developer’s point of view… it is out of stasis now because gentrification is the new global phenomenon”[4] and therefore, a likely useful notion and tactic for specific urban processes based on distancing as a surface-level transformation.[5] Purgatory, like limbo, is a state of being in between. With purgatory, there is a declared direction to go, as in—to purge. But with limbo, there is not. It is as it is.

Altered Sites #7 (1998) by Manuel Acevedo. Pencil and ink on gelatin-silver print, 11 x 14in. Reprinted inkjet print, 40 x 60in (2016). Limited edition of 3 and an artist proof. American Art, Smithsonian Collection. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Described another way, limbo might be thought of as the “castoff” that Kevin Blythe Sampson has identified[6]. One element that has brought together all interviewed artists so far is their discernment in taking what the dominant logic has discarded. This may be the reclaimed bones and relics of Sampson’s work, the ingenuity of cardboard and plastic bags as in the art of Gladys Barker Grauer[7] or the capturing of what has disappeared or falsified into “nothing here before”[8] as seen in Melgar’s photography. Also, James Wilson says that in his eyes, Newark is rather a purgatory “where worlds collide.”[9] In a way, this is an inversion itself—of the sight developers have placed on a city they wish to take because of its life.[10] This bleeds into the art of Manuel Acevedo, whose perspective speaks to the forgotten parts of Newark. Such a work of discernment deepens to ask what, in reality, are the fictitious parts of all that is Newark.

Asked about the nature of Newark’s decay, Acevedo says:

“There are obvious forms of decay. For example, if you see a shell of a church, removed of all of the old pews, holes in the roofs, and windows that are broken—you go inside, you see what’s there. You might access it through the roof or a window. This makes urban decay. But it becomes inspiration in my eyes. Those kind of poetic images. It’s intimate, so I think there is something about it that psychologically draws me to it. It speaks to me. Some things are in the architectural details. But in my mind, I redefine it. I never saw it as decay, or what is known as decay, because decay is something that is poetic. But the ruins embodied something greater than me. There’s something spiritual about it. There was no physical, human presence. It’s charged. There was energy there, even if it’s maybe something I projected into there. That is fine. It is a perception that changes. It is how to cope with the psychological implications of the landscape. Worn, torn, stressed, or weathered. I trust that I internalized something. Something much greater than I can describe sometimes.”

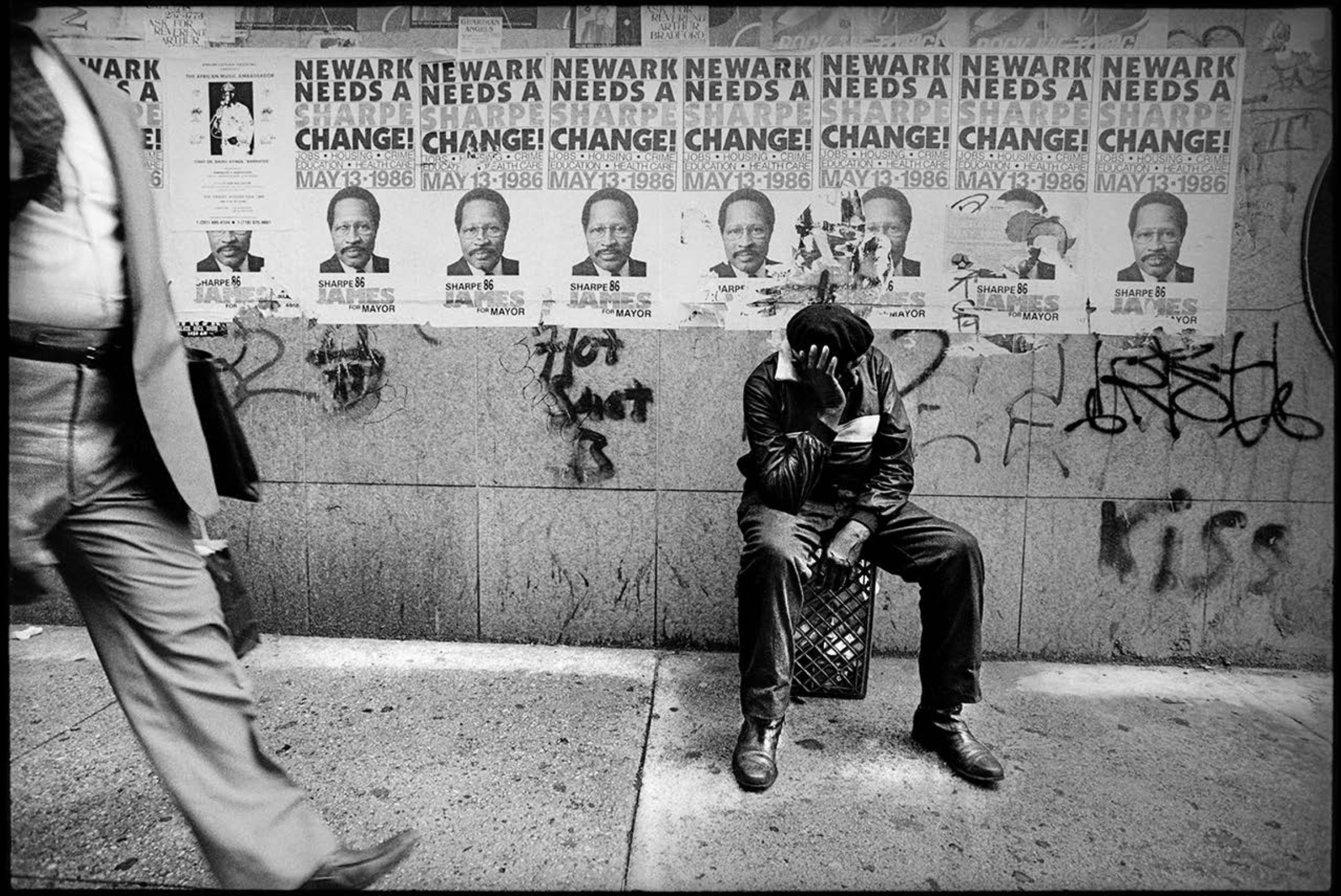

How Sharpe? from The Wards of Newark (1982−87) by Manuel Acevedo. Inkjet print, 11 x 17in. Gelatin-silver prints 11 x 14in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

The process of inversion reveals that Newark is an unforgotten ground. Acevedo completed The Wards of Newark (1982−87) between the 1978 Newark Master Plan and the current 2012 Plan[11]. At that time, he was working as a freelance photographer for the municipality[12] that re-branded Newark as “The Renaissance City.” The concept of “The Renaissance City” is based on an idealized, unique, individual point of view, taken from the Renaissance itself. Thought of as the ideal city, the Renaissance represents the birth of finance and a place for individuals in society. Such a viewpoint is where bodies soil the perspective.

Newark’s 1978 Plan stated that in 1971 the City had received under $1 million in restricted Federal funds and by 1976 had reached more than $40 million.[13] Acevedo says, that “the biggest problem with the city is that there are no opportunities for residents to move along with all the changes in their lives.” This foretells a piece of Newark’s story during the 80s. “Image” was cited first as one of the “most important issues or ‘causal’ factors to be affected by public action”—“causal” in that this situation affected the “economic development environment and, ultimately, the vitality of the City.”[14] The Plan considered that “Newark’s image is based on perceptions derived from conditions, experience, and information—both real and imagined. While the general image of the City has improved over the past several years, to those familiar with the City, continued efforts must be made to improve both local and ‘outside’ perceptions of that image.”[15] From this place, the active sight from others met the active eye of Acevedo to tell a story of their own.

The 1978 Plan foresaw a continual population decline in Newark. The City, at the time, had anticipated that “Newark’s school age population will drop by approximately 45% between 1977 and 1990”—so much so that “this trend cannot continue, and unless there is a major change in birth rate, or in-migration occurs in significant numbers, the school age population in Newark will drop to between 35 and 40 thousand by 1990.”[16] The 1978 Plan stressed that financial services, in part, had stabilized a process of de-industrialization. Yet this questions what, in reality, could a nexus of financial services bring to Newark. In a context of a foreseen, real political economy crisis, the administration responded with a top-down campaign based on image that looked at the city as an object to be marketed. Acevedo, as a photographer, did the opposite by expressing the dignity of Newark’s people as subjects.

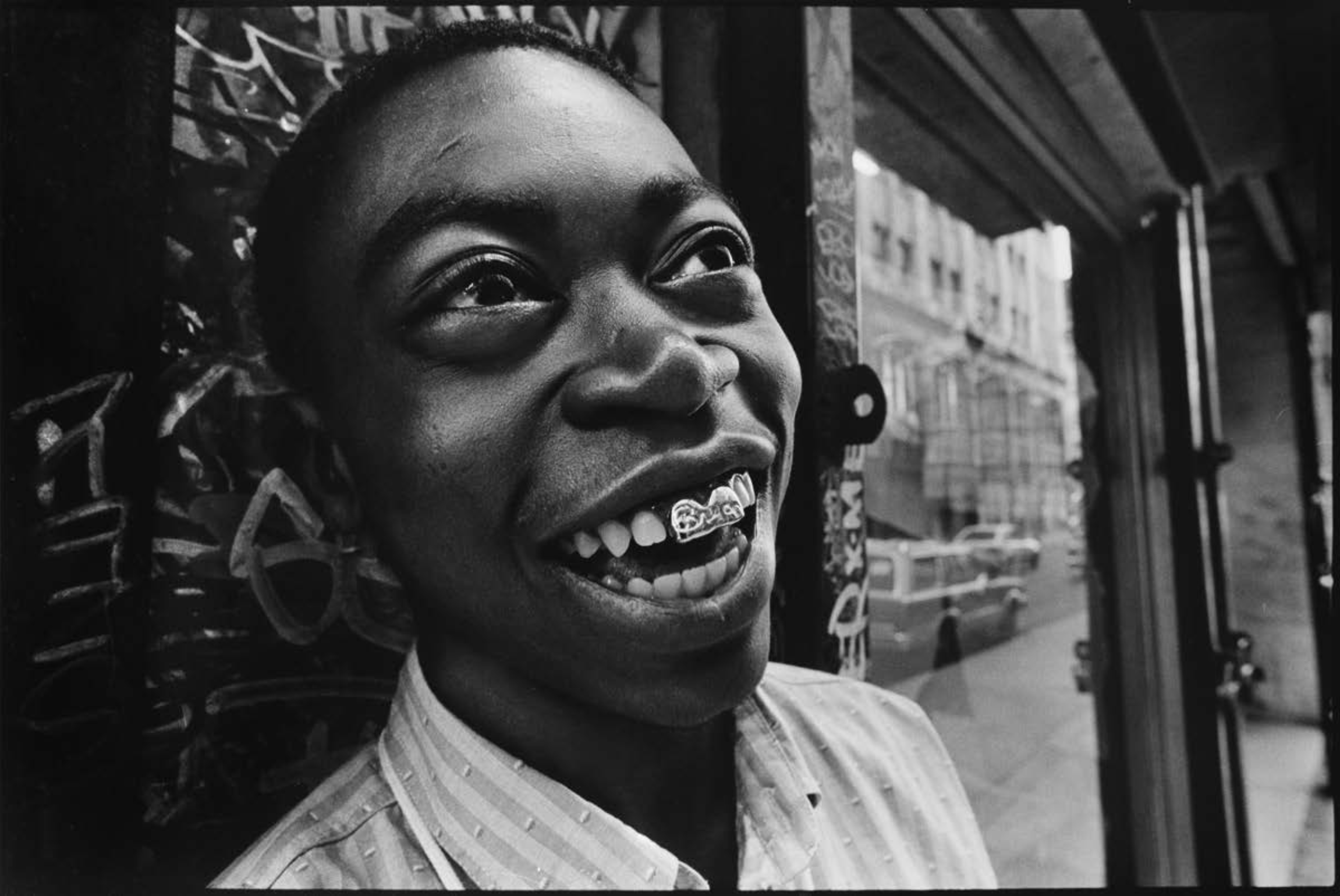

Bryan from The Wards of Newark (1982−87) by Manuel Acevedo. Inkjet print, 11 x 17in. Gelatin-silver prints 11 x 14in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Limbo, as something that seems static, has little to do with the aesthetic and ecstatic, out-of-place development happening in Newark today. Displacement, as in the aforementioned purgatory interpretation by Melgar, is “out of stasis”[17] and arises from a developer’s point of view. Limbo, however—stands in place. Both purgatory and limbo highlight a point of view, where body tells the difference. Newark may be in purgatory or limbo—but both are Newark. Both an alive organism and a cadaver can be considered body, according to the point of view. Acevedo, in states of either limbo or decay, highlights the out-of-place, superficial changes happening to the body of Newark:

“I do a reading of the derelict landscape. Where I create, I decide to make a new façade or a new structure. In Newark, I can imagine a new building, but in decay. I would see into the new structure—from the initial structure into the new. I keep a reminder of what was there. I keep the façade, the infrastructure or the skeleton structure, if you want to call it decay, to remind us of what has transpired and happened, and what is now present. Such as with Alter Sites, where I take what is now a package. I take an empty landscape and draw in it. This is significant and allows me to visualize a new space. A reminder of what is in between the space. This includes a drawing or structure in a derelict space or place. The question is always: is it in between what is constructed and deconstructed or dismantled? The way I see it, the completion is relative.”

Acevedo’s vantage point meets the sight of many inhabiting perspectives, being within Newark’s active body. This contrasts with what he has internalized as static to show what is alive, and with the absolute perspective of urban development. The latter shows up as just a superficial body.

The common law doctrine, escheat, ensures that land without an heir is never left in a “limbo” state. Escheat is a French medieval term that comes from the Latin excadere.[18] In Latin, cadere means “to fall”—as in cadaver, while ex means “out” or “away”—as in the displaced exstasis. Under the doctrine, a land with unrecognized heirs literally “falls out.” Escheat, thus, is the process of transferring land in “limbo” to the crown, state—or in the case of Newark, to capital. The word “cheat” (a deceptive act based on forfeited property) comes from escheat[19]. Despite the presumed absence of feudalism in the United States, escheat applies today, yet appears as some kind of lapse in time and continuity. The excadere, if prevented, does not “fall out” into the hands of someone else but transfers to the power. Then, there is no such thing as a “limbo” in “stasis.”

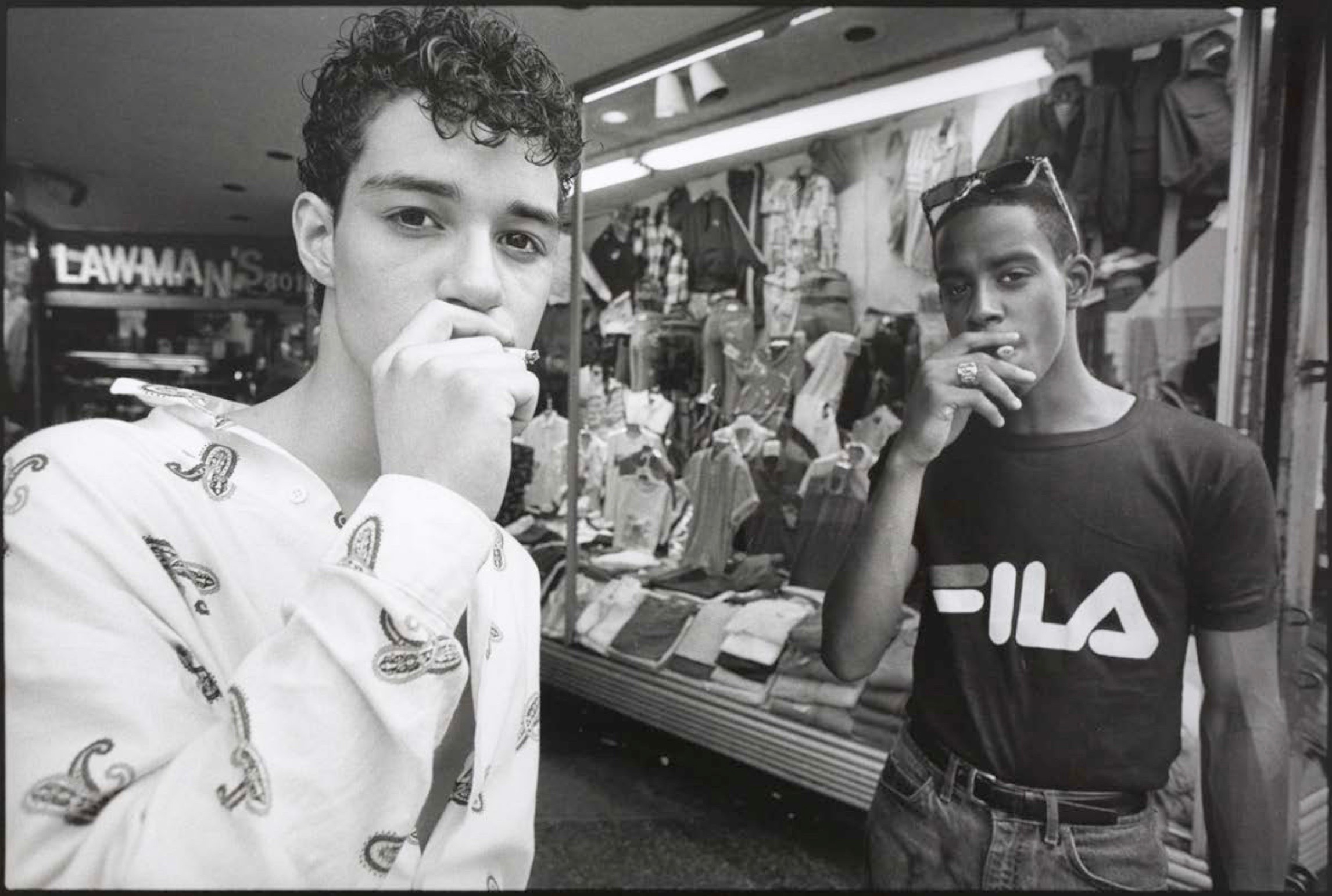

Lawman’s Cigarette Break from The Wards of Newark (1982−87) by Manuel Acevedo. Inkjet print, 11 x 17in. Gelatin-silver prints 11 x 14in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

The people Acevedo photographed in The Wards of Newark (1982−87), whether or not they look directly at his camera, do so without participating in the general parade of spectacular images that we see today as a swarm on social media. Abundance of the camera today, regardless of the relationship between subject and object, has taken on a different quality based on interface and audience. Since The Wards of Newark (1982−87), society, overall, seems content to superficially edit and glaze over how they appear in front of a lens at the moment an image is taken. The greater access to images that we see today, the greater the kind of barriers that diverge from the honesty of Acevedo’s subjects and their relationship to him. The eyes of the young men in Lawman’s Cigarette Break provoke the photographer and even the observer of the photograph 30 years later—in a way that is now rarely found in people photographed directly by themselves or even someone else. The young men look at you instead of themselves, showing what is real. Such an act asks of its contrast, why one would want to show what is unreal. To show what is not there is to show what is hollow, and pretending to be full avoids showing authenticity. However, one shows what is real by not pretending to be full.

What is more is that Acevedo’s The Wards of Newark (1982−87) illuminates a post-1978 Newark Master Plan. As in today, if one is aware they are to be captured in time, watched during a moment, or critiqued by an appearance, as in the case of an urban development plan that progresses over time, then one might pose, formulate, or pretend for the sake of being liked to face less judgement in the eyes of others. This too inverts, but it has a face of distorted power within a concentration of power. Today, many cities share the same logic, appearance[20], and mechanized ways of being that are void of politics because they speak the same language of abstraction, of universal capital. The Wards of Newark (1982−87) shows that Acevedo articulates the difference.

Despite the current homogeneous qualities of abstraction that have become of cities, Newark too, shows the difference. In photography, as in visualization, Manuel deciphers what is real and what is not. Perception, and his feeling of the urban environment, demands the question of what is imaginary about a place—as it is—not as something that needs to be made or told what is has while in the hands of someone else. Acevedo still finds it preserved in a shell of a church or barren landscape as the expression of a potentially extinguishable language. Acevedo’s body of work is alive in that it is a point of passage—not for human-circulated consumption[21]—but a passage that transforms as opposed to conceals. It is the static versus the non-static.

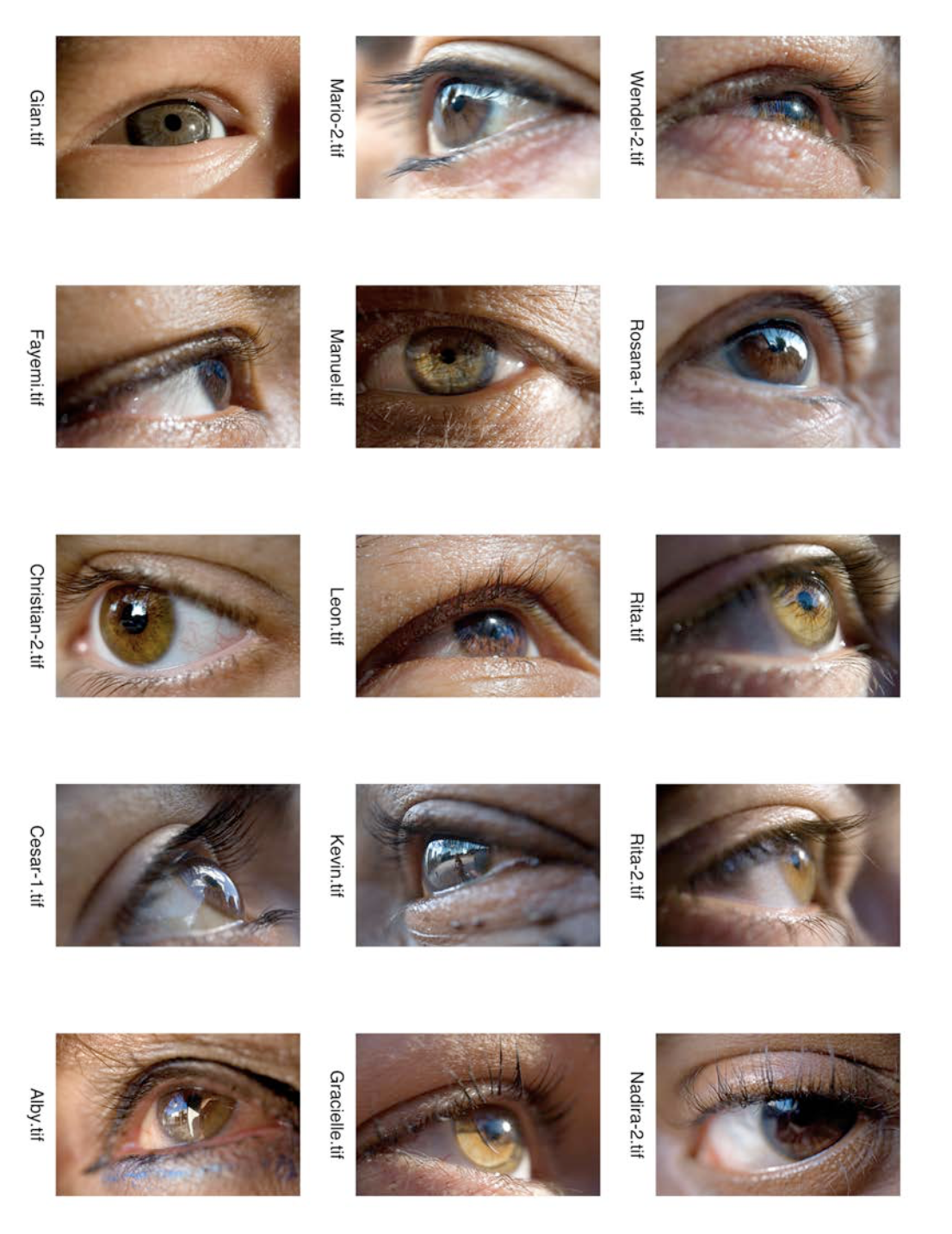

Eyes on You (Newark) (2013) by Manuel Acevedo. Inkjet prints on Sugarcane paper, 19 x 13in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Manuel Acevedo shows a reality from multiple visual perceptions. The inversion of a static state into dynamic, passive into active, and his relation between subject and object is still recognized today in works such as Eyes on You (Newark) (2013), and the way he turns houses into camerae obscurae. Often uncited, the origin of camera obscura comes from Ibn Al-Hacen whose Book of Optics c. 1029 A.D. explained how we see light reflected from an object. This discovery comes before the camera itself. It is a concept that would not be retaken until the Renaissance. Camera obscura touches a relationship between subject and object because it inverts the action of subjective sight into the action of the object towards the subject. It is here where the body is the action in that it tells the difference between passive and active. Here is also where the inversion in Acevedo’s work of today takes place, based on how experience is shaped, over time, by the light and movement of a visual language that “transforms flat, static images into active spaces of experimentation”—one that is void of a falling, out-of-place lapse. This is seen in the Artist’s text-based architectonics that confront the covert qualities of overt language, and between myth and reality. It touches also on the past, where Acevedo tells that his unprinted, bare negatives of The Wards of Newark (1982−87), in retrospect, show a greater body of work than one might expect.

If Acevedo’s art were a camera obscura, looking at Newark—one cannot help but wonder what else might be upside down. Manuel Acevedo recognizes the concrete inversion of life in Newark, the one that has begun to show itself among “projects that will transform the face of Newark.”[22] Reality, when consumed becomes unreality. The life of people does not create such an effect. An urban transformation driven by capitalist interests does—to the point where life consumes itself and where non-being is the commodity.

SB: Why did you move to the Bronx, and what is your relation to Newark?

MA: I was born and raised in Newark, New Jersey. When I officially moved to New York City in 2003, I continued to occupy a studio in an old (since demolished) piano factory in Elizabeth and visited Newark regularly. My love brought me to the Bronx. My partner, Mariana, and I have made the West Bronx home for our family with two boys, Neco and Gian.

There are many interesting parallels between Newark and the Bronx—demographics, socio-political, and economic ties. It is rich in urban folklore and tales like Newark. The Bronx is the birthplace of much of Hip Hop’s creative and political culture, as we know it. Both cities have areas in the physical layout that feel similar, though, believe it or not, the Bronx seems to possess much more green space and open terrain to explore. They both share the rise, fall, and resurrection of American cities.

SB: And where did you live in Queens?

MA: I moved to Queens in the early 2000s when I got married and later divorced. I lived in Sunnyside, Queens—which has its own complex beauty with hundreds of languages and ethnic groups documented throughout the borough. I enjoyed walking the neighborhoods but haven’t been back since I moved to the Bronx.

SB: Can you speak about your art and how it relates to Newark?

MA: As a child, I loved my Father’s blue ballpoint pens and drew on line paper. I channeled childhood trauma of the first police arrest in my family. I was three years old at the time, but the event remains just as vivid. I would play back a revision of the event and invented drawings of shoot-out scenes from an unidentified individual on a rooftop firing bullets as police on the ground level fired back. Why would the person on the rooftop be firing at the police? The haunting reality was followed by storybooks like my first pop-up book of Hansel and Gretel which I brought on visits to Puerto Rico as a youth… then horror films, Godzilla, King Kong, and car culture inspired my drawings later on. In addition, one of my favorite uncles, Tavo who was a brilliant self-educated inventor, inspired my creativity. He had a great vision, customized VW in the 70s before it was popular in the States in East Coast popular car culture, much earlier than I can remember in the States. He even made his known front tooth with a post from a epoxy compound.

Fast forward—I was fourteen years old and I was serious about my art. During my first year of high school, I met Mr. K, my art teacher and mentor. He taught drawing, design, serigraphy, and photography. I really enjoyed mechanical drawing techniques as well as printmaking. I was exposed to Anima by my friend Dean in 1980 and learned about processing B/W film soon after. By the time I transferred to Arts High in my junior year (Mr. K accepted a job at Arts High as well). I was thinking about social commentary before I even knew what it was. My neighborhood was in flux. The Italian, Irish, and Ukrainian residents were moving out as the majority shifted to African and Spanish-speaking Caribbean residents. My photography reflected this community as I moved away from being a graphic artist temporarily. I wanted to see my friends and neighborhood happening on film and print. The images ranged from child’s play to family portraits.

The Newark People series was born, and later I renamed it The Wards of Newark after a conversation with Charles Biasiny-Rivera, one of the founders of the En Foco Bronx-based photographic organization. There are many beautiful sequential narratives in my negatives that I’ve never printed as contacts dated back to the 1980s. In making photography, I personally reflected on the place where I lived and the people I lived with to document the changes, nuances, and happenings in the hood. I learned more about my community through photography, and I had a great urge to preserve it.

I lived between the photography and graffiti art world, the graffiti writers. I wrote PRINS, NAM (No Apparent Motive). I became interested in Newark community murals and Mexican muralists, which had a built-in support for work with a social context. At 18–19 years old, I already had a pretty clear vision of my photography and direction. I continued to work on the Newark People series. By 1987, I received my first New Jersey State Arts Council photography grant. I continued to make images, I didn’t print much, I never printed enough. I have the negatives. It’s a strong body of work in retrospect. Now when I look back at that work, I edited my images down at the time and denied the side of the photography that was more like essay work. Many narratives were exposed and fixed on film and never printed—but I don’t have any regrets. I was inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Decisive Moment, where everything is captured just before or after a moment. The image became much more of a preoccupation than the potential of the photo essay. Now, I see images that could have been printed and a stronger body of work than the single image.

I didn’t even know what I had. I was not an organized person, but I am a multidisciplinary person perpetually engaged in multiple projects. I became obsessed with working, accumulating images and drawings, but never branded myself. I developed within a global community of artists, and participated in some local art while finding my community in Newark. My art and identity as an artist is a product of these Newark encounters and self-sourced accumulations.

SB: How do you support the freedom of your art? How do you make a living?

MA: I’ve sustained freedom in pursuing a passion that has nothing to do with a marketplace.

Throughout my artistic career (I sold my first painting at age 17) I have failed to brand myself, so I’ve always felt liberated. For better or worse, I never concentrated on the market because my drive to create produced a sort of uninhibited frenzy. The advantage to being in a constant state of production is the accumulation of work that meets my self-imposed standard. I have had the freedom of creating bodies of work and commissions while working sporadically as an artist educator.

SB: What do you teach?

MA: Throughout my career I have taught primarily 2-D or 3-D art, design, traditional flipbook and stop-motion animation at museums and cultural institutions. I’ve been working for over 20 years in the field of arts education. I currently work freelance as an Artist Educator with the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in collaboration with the New York City Department of Education’s (NYC DOE’s) Alternative Learning Center (ALC). The program allows me to present design challenges and art processes as a medium for expression to middle and high school students who have been suspended from their regular NYC schools.

SB: Until you, I had never heard about Newark’s Puerto Rican uprisings of the 70s or what followed in the 80s. What are the forgotten parts of Newark? Can you talk about some of them?

MA: I was a young boy when events related to the uprising happened—maybe seven years old? Though my neighborhood in the West Ward wasn’t all Boricua (Puerto Rican), the stories were a known part of Newark urban folklore. According to my father, rising tensions erupted when a young girl was struck by a police officer on horseback at Branch Brook Park in the North Ward during the Puerto Rican Day festivities. I remember my Father driving a station wagon he purchased back in the day. It was a used police vehicle with a black and white police emblem still on it. He had the vehicle painted in a metallic gold. One day, he was driving through downtown as the police officers were mounted on horseback. He kept an iron pipe tucked under the back seat. A lot of traumatic events were internalized in my immediate and extended family. On occasion, I would hear stories. It’s possible they’ve changed as I remember them, my memory plays tricks on me.

There is little documentation of the Boricuas uprisings in Newark[23]. I did, however, come across a very powerful and beautiful image of an angry boy about 12–14 years old standing on a car that had been destroyed and a blaze is behind him. There was a lot of tension with Newark residents and the police that continues to present—with armed officials abusing their power and exercising prejudice against the black and brown community. Remember, the city of Newark and its residents were living in the aftermath of 1967 uprising and trauma, like many urban cities in the USA. I can imagine the affects it had on the folks in the North Ward. According to related experiences and studies on the uprisings, many African and Caribbean diaspora community leaders and residents felt disenfranchised in Newark. Newark was one of the first majority African and Caribbean diaspora cities in America. The leadership in City Hall didn’t reflect the population until 1970 when Gibson was elected in a runoff election. The 70s–80s was a turbulent period for Newark residents and politicians alike.

SB: Is Newark a city and why?

MA: It’s what I would call a multicity—very large, with many identities. Each of Newark’s five Wards is complex and culturally rich, with a handful of religions and identities. The West Ward, which I wrote about in HYCIDE[24] and where I was raised, was an interesting mix of people. There were Italian, Irish, and Ukrainian, only a few Boricua families within a community, and other folks of the African Diaspora from the Caribbean and the South. They were speakers of other languages and dialects. Other Wards represented their own multiplicity within the multi-city.

SB: Is Newark rural?

MA: Newark has a small town feel. Its sparsely populated downtown is quickly changing. Its outside limits once designated for commercial and industrial use are being converted into residential centers with less open spaces.

There are neighborhoods with derelict properties that I visited that felt barren, rural. It’s a particular kind of beauty I will miss it as it continues to be occupied with new developments. I remember revisiting Prince Street with sparse lots with a few vacant homes that were left alone in the 80s. They had returned to nature with growth on them and decay. Once the homes were taken down, they were made into big mounds and over the years transformed into an overgrown landscape. This is what I considered rural in urban places. As nature took over, there were little signs of what was once an urban environment.

SB: What is home?

MA: In few words: family and security. Ensuring these two primary elements were in place was at the forefront of my home experience growing up. Aside from early factory jobs and odd jobs, my mother (a skilled seamstress) and my father stayed very close to home. With five children to rear, my parents turned to the supplementary income of la bolita—a kind of lottery common in the neighborhood. It was considered illegal, however it supported many families long before you could play Pick 3, 4, or Lotto. It was about selling chances and buying numbers, so if your number hits, in the evening you may win 150 dollars if you played a dollar. This nation’s Wall Street was built on selling chances. Because my parents were taking a chance by running an in-home operation, there were custom security measures throughout our house such as reinforcement wooden bars and multiple locks on our doors. The doors typified in my home became the subject of interest as I transitioned from The Wards of Newark project into semi-auto biographical work—which included paintings on discarded doors, drawings, maquettes, installations, and photographic images depicting intimate scenes of home.

SB: What if urban renewal, urban decay, and the recent piecemeal development would never have happened in Newark?

MA: It’s kind of a trick question. There is no such phenomena. Urban renewal and urban decay are a big part of the way cities transition and change, and this affects all living creatures.

Urban renewal and decay has informed the envisioned spaces of my work.

I was attracted to certain places because of their obscurity. I wanted to shed light on places I frequented that seemed hidden from the general public. In The Poetics of Space French philosopher Gaston Bachelard questions whether we can define such spaces as abstract, poetic, immersive, psychological, intimate, or magical. With the camera I was able to capture the symbolic void—an unknown phenomena. In my experience, the unknown lies between places of urban decay and renewal. Throughout the 80s and 90s I accumulated photographic records of spaces in limbo. I never knew if they were being taken apart or being constructed, but the photograph bears witness to the space’s potential—past, present or future.

Manuel Acevedo has exhibited in the United States and internationally for over 25 years. Solo exhibitions include the Bronx River Art Center, New York City, the Latino Cultural Center, Dallas, Texas, and the Jersey City Museum, Jersey City, New Jersey. Awards and residencies are from the Joan Mitchell Foundation; Visual Artist Network; Longwood Arts Project; Mid-Atlantic Foundation; Museum of Art & Design (Artist Studios), and the Studio Museum in Harlem, AIR.

Recent exhibitions include: The 5 Wards—a group exhibition curated by Akintola Hanif at City Without Walls and Seton Hall University of Law, both of Newark; Playing with Fire at El Museo del Barrio, New York City; Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art (traveling exhibition) and Down These Mean Streets: Community and Place in Urban Photography, both curated by E. Carmen Ramos at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Renwick Gallery) in Washington, D.C.

In Newark, Acevedo is working with artists on a PSEG Art Wall project with the City of Newark Fairmont Station. The Newark Museum recently acquired Acevedo’s Altered Sites series (3 works) of Newark’s Military Park (2004) with a fourth silver print (before and after) as a gift from the Artist. Acevedo is also creating an architectonic mural of the word Newark.

More on Manuel Acevedo can be found at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (on Altered Sites #7), HYCIDE—The Wards of Newark and Decisive Moment; Culture Hall, and BX200.

Footnotes:

[1] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 13−15.

[2] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark [All Issue Photography]. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015).

[3] Melgar, C. (2017, February 20). Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/cesar-melgar-razing-history-make-surface-lots-famous-newark-administration-pastime/

[4] Ibidem.

[5] Pachirat, T. (2011). Every twelve seconds: Industrialized slaughter and the politics of sight. (p. 11). New Haven: Yale University Press.

[6] Sampson, K. B. (2017, January 15). Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/kevin-blythe-sampson-newark-danger-realness-power-history/

[7] Grauer, G. B. (2017, February 1). Gladys Barker Grauer—“Newark sensed it.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/gladys-barker-grauer-newark-sensed/

[8] Melgar, C. (2017, February 20). Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/cesar-melgar-razing-history-make-surface-lots-famous-newark-administration-pastime/

[9] Wilson, J. (2017, August 29). James Wilson—Newark, “when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/james-wilson-newark-hood-youve-never-felt-home/

[10] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 13. Melgar’s Newark photographs for the rural Journal of Biourbanism “represent a city that will be starkly different soon, now that commercial and real estate interests have put their scope on our resilient, historic urban landscape.”

[11] Bissen, S. (2016, January 15). Newark—on heterogenesis of urban decay. International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/newark-heterogenesis-urban-decay/

[12] Acevedo, M. & Stetler, C. (n.d.). The wards of Newark. HYCIDE. Retrieved from http://hycide.com/THE-WARDS-OF-NEWARK

[13] See Bissen, S. (2016, January 15). Newark—on heterogenesis of urban decay. International Society of Biourbanism from The Mayor’s Policy and Development Office. (1978). Newark master plan. (“Summary”) (p. 2). City of Newark: Office of Planning, Zoning & Sustainability. Retrieved from https://planitnewark.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/1980newarkmasterplan.pdf

[14] “Causal Factor” as a planning process term is defined for both citizens and public officials as follows, “1.2 Approach”: “[Causal] Factor—A condition associated with the economic development environment which can encourage or deter local economic growth (e.g., availability of land, cost of labor, city image, quality of city services, etc.).” Ibidem, pp. 1−8.

For more on “Image” in the 1978 Newark Master Plan, see:

Recommendations for “2.1.1 Master Plan Goals and Priorities”: “The need for coordinated land-use and development focuses most heavily upon the ‘central corridor’ of the City—the north/south corridor extending through and including the central area of Newark. This area is bounded by McCarter Highway on the East, Hawthorne Avenue on the South, Route 280 on the North, and Irvine Turner Boulevard on the West. This is the City’s most intensively developed area and provides major resources for services and employment and a focus for much of the community’s shopping, cultural, business, financial, education, entertainment, and governmental activities. To a large extent, the image and appearance of Newark is established by this area.” Ibidem, pp. 2-3−2-5.

In relation to transportation, “2.2 Land-use Element”: “A street’s attractiveness and the presence of other amenities (or lack of them) are important qualities affecting the desirability of residential neighborhoods and commercial districts. These routes can affect the well-being and the image of the entire community.” Ibidem, pp. 2−9.

Specific City policies from “3.3.1 Physical Development Policies”: “Attract new major service sector activities by providing adequate public support to the existing base while improving the external ‘image’ of Newark.” Ibidem, pp. 3−17, and “Table 3.2: Relationship of Causal Factors to Elements of the Economic Development Strategy” as a “Community Related Causal Factor” in relation to “Goals (Strategy Elements)”—“Image” as it relates to “Stabilize Existing Economic Base; Encourage Economic Growth; Improve Resident Economic Opportunities.” Ibidem, pp. 3−12.

Predating the current 2012 Master Plan’s frame for Newark as a 24/7 destination to live, work, and play, see “2.8 Conservation/Environmental Element” prescription: “Upgrade the character and quality of the City as a place in which to live and work—the visual, aesthetic, and image-related features of the City.” Ibidem, pp. 2−87.

[15] In “Summary.” Ibidem, p. 2.

[16] Ibidem, pp. 2−67.

[17] Melgar, C. (2017, February 20). Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/cesar-melgar-razing-history-make-surface-lots-famous-newark-administration-pastime/

[18] Online Etymology Dictionary. (2017). Escheat. Retrieved from http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=escheat

[19] Online Etymology Dictionary. (2017). Cheat. Retrieved from http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=cheat

[20] See Newark’s current Master Plan on Greenpoint, Brooklyn in New York and Savannah, Georgia as models for Newark. The Newark Central Planning Board. (2012, September 24). Newark’s master plan: Our city our future (Vol. 1, pp. 46−47). City of Newark: Office of Planning, Zoning & Sustainability. Retrieved from https://ndex.ci.newark.nj.us/dsweb/Get/Document-515469/econ_MstrPlan_2012_vol2.pdf

[21] Melgar, C. (2017, February 20). Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/cesar-melgar-razing-history-make-surface-lots-famous-newark-administration-pastime/

[22] NJ.com. (2016, December 19). 12 projects that will change the face of Newark. NJ.com.

Retrieved from http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2016/12/a_building_boom_in_newark_heres_a_dozen_big_projec.html

[23] Carter, B. (2016, March 1). Newark archivist revives lost history of Puerto Rican riots. NJ.com. http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2016/03/newark_archivist_revives_lost_history_of_puerto_ri.html

[24] Acevedo, M. (2016). Decisive moment. HYCIDE: The 5 wards. Retrieved from http://thefivewards.com/2016/12/16/decisive-moment-2/

For further study, see: Newark—On Heterogenesis of Urban Decay