by Sara Bissen

Gladys Barker Grauer, Newark. (2015). Photograph by Colleen Gutwein. Image courtesy of Gladys Barker Grauer.

NEWARK WITHHELD

Newark Withheld is a series by Sara Bissen about Newark, New Jersey today, as seen through the eyes of its long-standing artists.

Opened by Kevin Blythe Sampson, Newark Withheld initiates a discussion by local artists in relation to the transformation of their city. This series extends from the photographic work of Cesar Melgar in Newark,[1] featured in the rural issue of the Journal of Biourbanism.[2]

ARTISTS

Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.”

Gladys Barker Grauer—“Newark sensed it.”

Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.”

James Wilson—Newark, “when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home.”

German Pitre—“Newark has always been known for that edginess.”

—a closing with Lauren Sampson

Interview (December 20, 2016) with Gladys Barker Grauer by Sara Bissen

Gladys Barker Grauer is a root in Newark.

Born in 1923 in Cincinnati, Ohio, Grauer grew up in Chicago’s South Side, where she later studied at the Art Institute.

She moved to Newark with her husband in the early 1950s. Looking at the history of Newark—from its seasons of mobility and decay to its renewals and revitalizations—Gladys Barker Grauer has seen it all in both the moment and after.

Grauer’s art focuses on the human experience that is marginalized by those who possess wealth and power. Poverty, homelessness, and conflict are thus at the center of her work. Since a young age, she has had the curiosity and initiative to take things apart and put them back together again. To this day, at the age of 93, such acts are evident in her work. Grauer possesses the sensitivity and dexterity of working with what she encounters every day in Newark.

Of her artwork, Gladys states:

“I believe artists are recorders of events, society, and the culture in which they live. My art expresses my reaction to and interaction with the struggle of all people for survival. This struggle is motivated by the optimism of people for their intellectual, financial, social, political, and physical survival. I was inspired to create art with corrugate and plastic bags by the ingenuity of the urban homeless to convert corrugated boxes into mattresses, blankets, and insulation. To make plastic bags their luggage, rain coats, rain hats, waterproof boots.”

The Bedroom (1997) by Gladys Barker Grauer. Gouache and Corrugated Boxes, 20 x 16in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Over the decades, she has painted about war, police brutality, and racism. During her activism, Gladys won a First Amendment case against Morris County, New Jersey in 2007 after two of her paintings were removed from an exhibition due to their subject matter.[3]

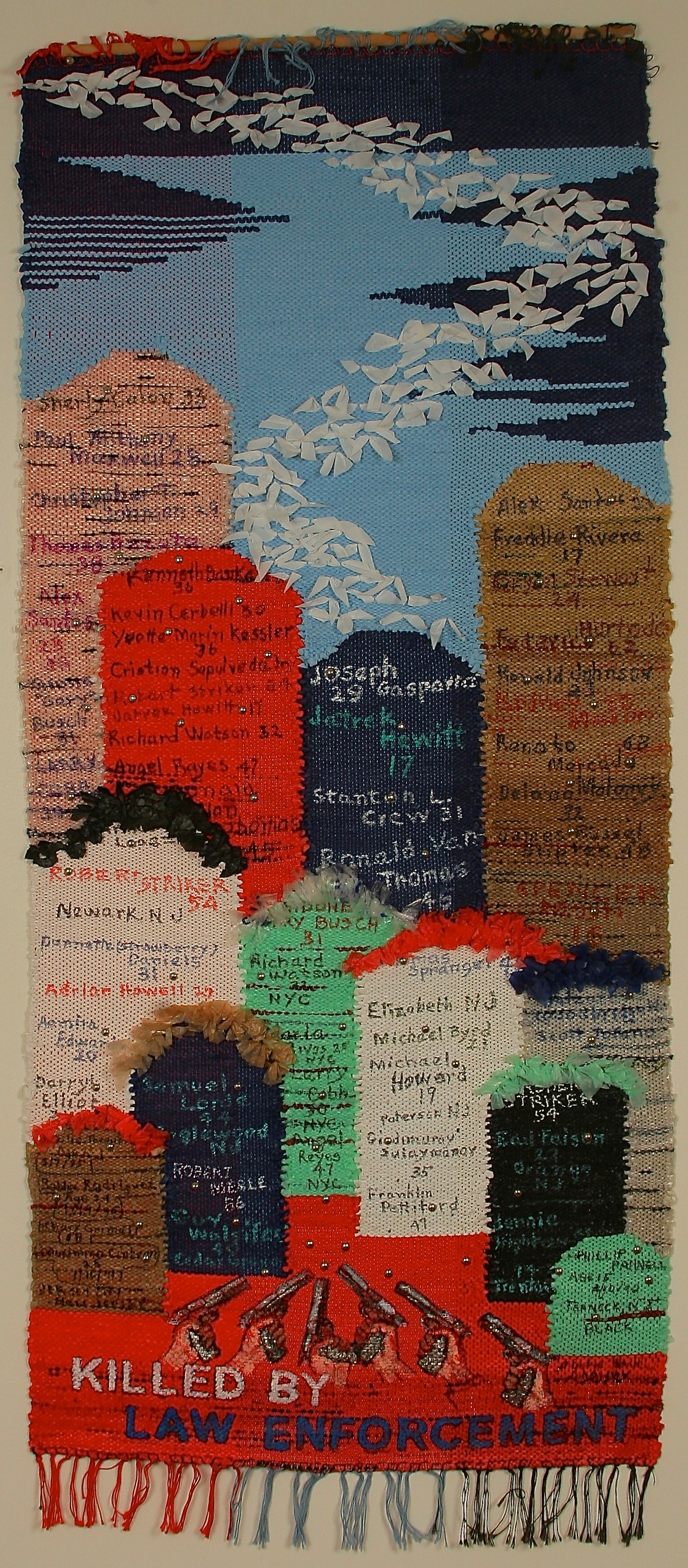

Killed By Law Enforcement (2014) by Gladys Barker Grauer. Woven Plastic Bags and Acrylic Paint, 49 x 31in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Grauer’s curiosity and action resonates in her voice. She has, over the years, brought a breath of life into Newark through her art—from the process of creating to the act of sharing with the residents of Newark. Whether being a mother, opening Newark’s first art gallery, or standing as a 1960 U.S. Senate nominee for New Jersey’s Socialist Workers Party,[4] Gladys kept her ground in her work and Newark neighborhood of Clinton Hill.

Gladys Barker Grauer, U.S. Senate Nominee from the Socialist Workers Party for New Jersey, speaking May 16, 1960 to The Militant.

As an artist, Grauer sees in Newark something that the dominant, urban logic does not. She had an early artistic process of dismantling things such as clocks and watches only to reunite them. This is reminiscent of poet Pier Paolo Pasolini, who in his Scritti Corsari (Corsair Works) insisted his readers take parts of that body of work that he had written, and for themselves, put the pieces back together in an understanding of the substance.[5] Pasolini, like Grauer, focused on a human experience marginalized by the power, yet unbound by ideology.

Justice, by Grauer, is a work of acrylic and woven plastic bags. In this piece, Grauer depicts the judicial story of 17-year-old African-American Trayvon Martin, who was shot to death, unarmed, on February 26, 2012 in Sanford, Florida by neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman. In the trial, Zimmerman was acquitted of murder, mobilizing the Black Lives Matter movement. In Grauer’s Justice, she shows the jurors in the Zimmerman murder case. The Artist shows that Lady Justice is no longer blind—Grauer says, “the bitch can see what she’s doing!” From Newark, Grauer has a sharp point of observation about universal and national issues.

Justice (2015) by Gladys Barker Grauer. Woven Plastic Bags and Acrylic, 9ft x 31in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Grauer’s work is rooted in both its content and its context. Observers may not see the relevance of her early process, from taking apart clocks and clothes or experimenting with soap to make it suitable for painting on photographs, to her later work of weaving plastic bags into tapestries. Such fragments, repetition, and moments of reorganizing and repurposing give ownership and understanding for oneself about the subject. Based on my own experience of living in Newark, I often felt lost among the major urban structures scattered across the city—placed in such a way that seems accidental—despite resulting from the dominant logic and forces of urban planning. Grauer’s joining of seemingly disparate parts is how she makes a city like Newark, a home.

Pasolini’s idea of the South—that is not a geographical South, but rather the pre-industrial, “fascinating like a myth” Souths of the world[6]—can be described in ways analogous to rurality as something that exists in challenge to the homogeneity of the contemporary city.[7] Grauer’s reaction and interaction with the urban struggle of human experience is present in her work, where she records and documents a colorful life. Such a life resists a varied seeping enclosure by outside forces over time. This reveals the remnants of a pre-industrial consciousness and allegria in contemporary Newark, such as in the primeval, positive force of the “proletarian life” that attracted Gramsci, according to Pasolini.[8]

I Wish the Rent Was Heaven Sent (1992) by Gladys Barker Grauer. Lithograph, 20 x 30in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

In fact, during the 1960s, Pasolini discussed his project of an unrealized work about the Souths of the world that would have included black ghettos of the United States. Grauer’s upbringing in Chicago, and the political conversations she had with her family at home and with her friends at school, led her, like Pasolini, “to see there were not only Black problems but world problems.”[9] Pasolini’s aim was to discuss the price of integration into global capitalism, which included the spiritual price of that integration.[10] Anyone who is sensitive to the hegemonic nature of cities knows such a cost very well. The Soul witnesses the resistance to such hegemony, while making the city really alive.[11]

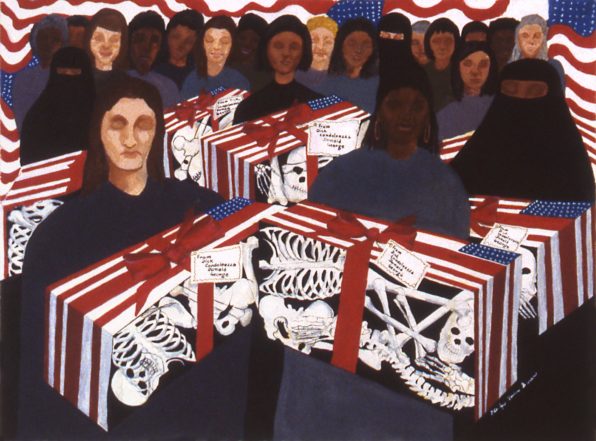

The Mother’s Day Gift from Dick, Condoleezza, Donald and George (2006) by Gladys Barker Grauer. Gouache, 24 x 36in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Such thoughts on the substance and reality of what Grauer’s art is actually about, may even be dismissed by those who do not experience that deep aspect of Newark. And in fact, this is what the outside tends to compromise when producing gentrification, real estate, and business disconnected from people. The optimism that arises from struggle in Grauer’s art is an expression of this vital force that she herself—as a Newarker—is part of.

SB: Why are you an artist?

GBG: Because that is all I can do—I was born to do this—even from the time I was a child. It has all led up to what I am doing now. I used to fix things that weren’t even broken—watches, clocks. I used to take clothes apart and resew them without a sewing machine.

Then in elementary school, I started drawing. In school, I had an art supervisor and she came once a year—this was in 4th or 5th grade. She gave us an assignment and she kept mine. I was very flattered. In my school, we really had nothing for art. By high school, we just got chalk and paper for our art classes—and you do what you do. I started going to the Art Institute of Chicago on Saturdays. It was not free, my family had to pay for the school. And that’s when I became serious about art. At that point, in high school, I realized I can do something—and something I like to do. I then started being an artist, from Saturday classes to full-time.

I also used to paint photographs. Family portraits—that’s what I was to paint on [laughs]. Were people upset? Of course! [Laughter]. I discovered that if you put your paintbrush in watercolor and soap, when it mixes it makes suds, and then the color will stick to the photograph. So I was painting these beautiful photographs. I was about 9 or 10 years old. It was a way for paint to stay on slick paper. I used the same technique for painting on magazines—I painted over the movie stars in magazines. Then I started drawing a copy of those same movie stars. Because I was able to draw a copy of them—that’s when my family knew that I was very talented.

When I started painting, I stopped painting photographs.

SB: Can you speak more about your art and the material that you use to create your art?

GBG: Well, I started with oil painting. I’m not sure why I moved away from oil. Maybe because it was too dry or too slow for me. I then tried gouache, watercolor, and different mediums. I usually work with a medium for 8–9 years. I’m not sure how much more I can work with it. I still work with watercolor, but I am now into acrylic on plastic bags—the plastic bags that you can get from the grocery store. I take strips of the plastic bag and weave them. I have worked with this material for about 4–5 years.

Before that, I was working with fabric, but I was not painting on fabric. I made tapestry—not with threads. What happens is that I go into different things. The Newark Museum had a workshop on weaving. It’s not my medium. I was more into rag weaving. My daughter could sew, and she had a lot of rags. I started buying fabric. The printed fabric was absolutely fascinating to me, it had a certain dimension. I would then weave landscapes—I made people figures.

But then, I needed a blue color, so I went into the plastic bags. The New York Times were coming in a blue bag, so I used that since I needed blue. I also use brown paper bags. What’s fascinating is that if you cut the brown paper bags into strips and dry them, they become stiff. I also used corrugated boxes before weaving. If you tear one layer of the corrugated cardboard boxes apart and put them together, it makes a difference. The color is the same, but the way the light hits it changes its color.

I’m fascinated with things that change. I take an accident and I make those accidents intentional. It takes you in a different direction.

The strips of corrugated cardboard were painted black, and it looked a lot like the beautiful dread locks on Black folks. Manuel Acevedo, when he was in high school, was a model for a portrait I did of him. I resisted gouache as a way to paint, then ink, because oil and water don’t mix. They washout without water pressure, so then you have to wait. When I used the corrugated strips on Manuel’s portrait, with his hair and all the people around him, he looked like Jesus Christ.

Manuel, “Manny,” as mentioned, was in high school at the time, so 17–18 years old. He was a student of one of my friends, Aleta Cardwell. I met many students being a teacher myself, and my friends brought many students.

SB: What brought you to Newark?

GBG: My husband. We lived in New York City, but we were working in New Jersey. We had a friend who lived in New Jersey and had moved to Newark. We said if our friend found us a place to live that we’d move. So we did.

We moved to Newark in 1951 or 1952.

SB: Why is Newark a fertile place for art?

GBG: When I came to Newark after a number of years living in New York City, I found that every weekend I used to go to New York City for art. In Newark, there was only the Newark Museum and the Newark Public Library. The library was absolutely fascinating. You could take whichever book, and check out a lot of things. A man named Mr. Dave had a picture file. Once, I was working on an NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) thing about boxcars, and the Scottsboro Boys[12] that were in the news. I could find magazines with pictures of the boxcars. I spent every weekend in the museum and library of Newark. But for art, I would go to New York City.

At that point, I had four children that got into everything—so I opened a gallery. There were no artists working in Newark, and there was not one art exhibition in Newark, except for the library. Then, you see what happened. All of a sudden, there were artists from East Orange, New York City, and all over the state. Ben Jones and big names were in Newark, but they had nowhere to exhibit their art. All these artists from New York came to me after the gallery rose. Newark became a center for artists, all African American and Latinos. There was a void and we filled that void. I filled it with the chance of exhibiting. My husband was working to support the gallery. I was the artist, and I didn’t know how to run a gallery. It started by accident, and the gallery lasted for 5 years.

About 8–10 years later, Liz Del Tufo came to me with the idea of a Newark Arts Council, so that laid the foundation for what came later. It functioned for about 5 years until we decided we had better get someone to do a study and tell us what to do. All of this laid the foundation for what’s happening in Newark right now.

Newark is a good place for blooming artists because it is not in competition with New York City. Newark is a nice place that is used to producing artists and entertainers. The Newark Arts High School is where many famous people have graduated. Newark is a comfortable, quiet place to be creative, and it has an audience. It’s not so much like New York City. There’s not as much market pressure, like in New York.

The market thing in New York made artists very competitive. At a gallery, everyone would be standing around, not looking at art, but standing against each other, looking for flattery. Newark is more honest. In Newark, people were much more honest. Artists are kinder to each other. Not that they don’t flare up, but they work together more than in New York City. It’s quieter. Newark is more humane.

SB: Living in Newark, I noticed elements of rurality (such as low population density, social relations based on trust, and urban decay) because of the overarching capitalist system. What do you think?

GBG: It’s a hard question. I grew up in Chicago and Newark to me had a certain resemblance, despite there were more trees. Yet, I can compare it to New York, specifically Manhattan. I still don’t know how I can put this comparison—Newark is a small town, but it has some big city images. It raises children, has neighborhoods, and you have more of a sense of belonging, and a sense of being part of it.

After the riots—that only affected a certain section of Newark, as far as destruction—there was a change in ethnicity. I don’t think it was bad. There was a lot of growth. In this country, in all the cities, usually businessmen in the black areas were Jewish because they were not welcome in Irish or Polish areas. Whatever problem—the businesses were where black people were shopping. This was in the Central Ward along streets where Jewish businesses were located. So, the police did not allow Blacks to go downtown during the riots. It was a social thing. People could not really justify who was destroying these stores, they just did it because this was thought to be our enemy. It was a bad business deal. And actually what happened was, for some reason, I don’t know why, but the Jews frantically moved out of Newark—and this was a great opportunity, a boom for the real estate industry. Jews outside Newark and Blacks in Newark were buying houses—a big money-making thing. Let me not go in this direction though, let’s stick to the art. Yet, you cannot separate art from society.

SB: Grauer’s work illuminates the lives of the urban homeless. Nowadays, what is Newark’s relation to homeless people? How has it changed over the years?

GBG: The homeless citizens are not allowed to wander the streets of Newark. They find refuge under the bridges, between Route 24 and the Passaic River, and Penn Station. The only time they venture to the streets is when meals are served at shelters and churches. Some use the computers in the Newark Public Library and Rutgers Library.

SB: What do you think is Newark’s role in the art world?

GBG: That’s a big question. I don’t know if it has a role more than any other city. From the 1940s to the 1950s, art was just booming here in Newark. Now, you have the Gateway situation—the Gateway Project Spaces by Rebecca Jampol. And Evonne Davis from Gallery Aferro, who had a dream.

Evonne opened the Aferro gallery 6–7 years ago. What happened was that those buildings were deserted along West Market. They were Jewish businesses and they were destroyed. Artists could have them rent-free for a year, but they had to renovate it. Some artists came and obtained a high price from the landlords because they were renovated. Evonne was the only one to stay. She created programs and an Artist in Residency in Newark. They have the most unselfish art in Newark. She made a fabulous work for the art of Newark—I have great admiration for her. Once a month in the summer, she has an art flea market where people come and buy stuff. That’s downtown, but even she is reaching out to the community, and this is the great thing of Newark. Evonne has projects within the neighborhoods. My love is art for the people, and art to the people.

Another project is Rebecca Jampol’s in the Gateway Center downtown, which is high class art from New York City.

SB: Can you speak about forms of resistance—in any form—both of today or of Newark’s past, and how this connects to artists in Newark?

GBG: There is a resistance of artists today. There is a conflict between the downtown artists and the other artists who have studios there. There’s a resistance or a conflict with Rebecca’s Gateway situation, with a certain high class—I don’t know a better word for describing it.

Three years ago, there was a whole mural project. Some of the murals were nice, some were good, and some were ridiculous. The person in charge did not have the competence for judging it. The walls were not primed, so half of the murals disappeared because they started peeling. The mural involved a lot of artists and some were high class. I am not in conflict with that, but Rebecca came up with the plan of bringing artists from Germany and all over, and they were to come and spend 6 months here and paint murals. I am a bad person—Kevin Sampson and I, and others jumped on it and said if you are going to do it you need to do it with local artists. Newark sensed it and the project stopped. Rebecca and the downtown group did a similar project several months ago with a mural on McCarter Highway. It was beautiful. It involved the downtown group and the Newark artists.

We had a social conflict. We have conflicts because there are two things here.

In Newark, we have a problem of people coming here. We see people come, make money, and then disappear. When we talk of conflict or rebellion, and Newark 50 some years ago—we resent people coming from elsewhere and setting up shop in downtown Newark. None of that is benefitting us. Like NJPAC (New Jersey Performing Arts Center), many people from Newark created it, but it’s for other people from Brooklyn and everywhere else.

They don’t know the feeling of the people here in Newark. I know the people, and I feel their resistance.

I felt this with the mural and McCarter Highway project. Rebecca had a project that included Newark artists. But what was before had no relation at all with Newark—people from outside coming and painting the walls—it completely excluded the Newark artists.

Kevin Sampson and I can have arguments, but on some issues like this, we come together.

SB: Much of the point of this series is about asking you, as the ones who understand Newark. Because as artists, you all have the sensitivity to understand the transformations happening here.

GBG: Oh yes, oh yes! We do. We are sensitive people.

Gladys Barker Grauer’s work has been exhibited in Newark, the United States of America, and around the world. Her art is in permanent collections at the Newark Museum, the Newark Public Library (Newark Special Collections Division), the National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Grauer’s work was currently featured in the group exhibition, “Modern Heroics: 75 Years of African-American Expressionism” at the Newark Museum, organized by Tricia Laughlin Bloom, PhD, Curator of American Art. Grauer has also, with Adrienne Wheeler, curated the newly opened exhibition, “Women in the World: A Visual Perspective” with Women in Media-Newark, on display at three locations—Rutgers University-Newark’s Paul Robeson Art Galleries, Monmouth University’s Pollak Gallery, and Newark’s New Jersey Performing Arts Center’s (NJPAC).

Grauer is the founder of Newark’s first art gallery, Aard Studio Gallery, which opened in 1971 on Bergen Street. She was also a founding member of the Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council, Black Woman in Visual Perspective, the New Jersey Chapter of the National Conference of Artists, and the Newark Arts Council. She has also served as a board member for the Theater of Universal Images and City Without Walls. Grauer was a teacher at the Essex County Vocational School. She has been an ArtReach mentor at City Without Walls.

Footnotes:

[1] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 13−15.

[2] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark [All Issue Photography]. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015).

[3] The two censored paintings are titled “Free Mumia Abu Jamal” and “Free Leonard Peltier.”

See Ragonese, L. (2008, February 2). Art hangs in Morristown, as censorship issue fades.

The Star-Ledger. Retrieved January 8, 2016 from http://www.nj.com/morristown/index.ssf/2008/02/art_hangs_in_morristown_as_cen.html

and National Coalition Against Censorship (NACA). Gladys Barker Grauer works censored in Morristown, NJ. Retrieved January 23, 2017 from http://www.thefileroom.org/documents/dyn/DisplayCase.cfm/id/1373

[4] See (1960, May 16). The Militant, XXIV(20). Retrieved January 23, 2017 from https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/1960/v24n20-may-16-1960-mil.pdf and (1960, October 31). Gladys Grauer hits duplicity on Civil Rights. The Militant, XXIV(39). Retrieved January 23, 2017 from http://www.themilitant.com/1960/2439/MIL2439.pdf

[5] Pasolini, P. P. (1990 [1975]). Scritti corsari. (p. 1). Milano: Garzanti.

[6] Speranza, P. (2016, February 17). Pasolini e i Sud del mondo. Voce delle Voci. Retrieved January 8, 2017 from http://www.lavocedellevoci.it/?p=4848

[7] Bissen, S. (2016). Editor’s Note. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 7−11.

[8] Pasolini, P. P. (1957). Le ceneri di Gramsci. (IV, pp. 8−10). Milano: Garzanti.

[9] Selma, C. (2011, May 31). WBGO celebrates ‘Made lemonade: Art of Gladys Barker Grauer’ with gala Thursday. Newark Patch. Retrieved January 8, 2017 from http://patch.com/new-jersey/newarknj/wbgo-celebrates-some-made-lemonade-art-of-gladys-barkbd72b1e56d

[10] Rohdie, S. (1995). The passion of Pier Paolo Pasolini. (p. 81). British Film Institute: London; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN.

[11] Sampson, K. B. (2017, January 15). Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/kevin-blythe-sampson-newark-danger-realness-power-history/

[12] Linder, D. (1999). Famous American trials: “The Scottsboro Boys” trial 1931−1939. Retrieved January 8, 2017 from http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scottsboro/scottsb.htm

For further study, see: Newark—on Heterogenesis of Urban Decay