by Sara Bissen

J. Wilson, Newark. (2017). Image courtesy of the Artist.

NEWARK WITHHELD

Newark Withheld is a series by Sara Bissen about Newark, New Jersey today, as seen through the eyes of its long-standing artists.

Opened by Kevin Blythe Sampson, Newark Withheld initiates a discussion by local artists in relation to the transformation of their city. This series extends from the photographic work of Cesar Melgar in Newark,[1] featured in the rural issue of the Journal of Biourbanism.[2]

ARTISTS

Kevin Blythe Sampson—“Newark is in danger because of its realness, power, and history.”

Gladys Barker Grauer—“Newark sensed it.”

Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.”

James Wilson—Newark, “when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home.”

German Pitre—“Newark has always been known for that edginess.”

—a closing with Lauren Sampson

Interview with James Wilson by Sara Bissen

James (J.) Wilson a.k.a. Scorebrx creates his art as a duty. In Newark, Wilson feels he speaks for the unspoken, the dispossessed youth, and the “signs of the times.”

Wilson, a graduate of Newark’s Arts High School, is today a guide for the young people he works with in the arts, and at the same time, a legendary teacher of Newark’s next generation of skateboarders. Because of this, the Artist is against the sale of the word “community.” James acknowledges the inauthentic nature and worn-out capacity that tends to rise from the term. “Community” in fact, as he points out, is nowadays useful for its ability to draw lines based on the direction of multiple agendas and the guiding principle of finance in a city. Finance has become one with urbanism.

James gives us an example of this, citing the design of a commuter tunnel that was built when he was a child. The tunnel was constructed in order to prohibit commuters (mostly white-collar) from New York City and the Eastern Coastal regions to get in touch with the grounds surrounding Newark Penn Station, which had been considered “dangerous.” This tunnel, as James saw, marked a limit between the life of Newark and the outsiders passing through.

Dock Bridge #1 (2016) by J. Wilson. Acrylic on Canvas, 20 x 30in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

At that time, James was living in the Garden Spires apartment complex, a “rough” social housing area in Newark’s Central Ward that is characterized by two towers near Branch Brook Park.[3] He thrived in this place where he felt as his own. He talks about how he played to hide within his own environment. In his creativity, James had layered his points of view and simulated situations of visibility and concealment. Here, even his eyes had become the eyes of many as he experimented with sight, shadow, and defense through unusual points of view. His ability to “avoid detection” gave him the freedom to move within Newark. Whereas, the avoiding commuter tunnel that restricts movement and thus freedom, seems to be the metaphorical opposite of his childhood play.

Urban design and real estate business have kept on drawing borders and pushing people from their homes in Newark’s transition and central areas. One result of this is a growing urban incapability for those that have not lived the roughness that the Artist appreciated, enjoyed, and coped with throughout his life. James provides a passage among those he teaches and creates with—because of his sense of deep Newark. It is possible that people coming in will be more shatterable because they will not have access, will not think of, the rough, deep Newark that has nourished Wilson.

James’ art is Newark—and it is a reflection of his awareness in it. The Artist portrays what he sees and offers a different kind of sociality because of it. This is grounded in what the Artist has, in actuality, either embraced or drawn for himself and others. Perhaps his duty, within Newark and therefore his art, comes from diminishing signs that have little meaning for many people. Wilson’s works are a series of many faces—where a face can be made of many other faces, which in turn, can be made of many others. This is a representation of an infinite layer based on where he is.

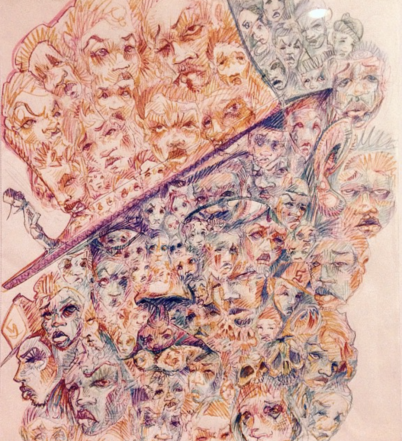

GCM 2 Series Sketch (2015) by J. Wilson. Colored Pencil on Paper, 11 x 20in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

At first glance, what is visible in Wilson’s GCM 2 Series Sketch (2015) is a portrait of one face. But looking closer, one face becomes many. Further in, there may be more faces within the many that journey into infinity, one beyond the other. Infinite dissolve ends the viewpoint of one over many, and then dissolves the point of where to look—forward or back, up or down, left or right. There are no lines to divide as the viewer chooses where and how to gaze. There is both a reverse and inverse perspective.

All at once, GCM 2 Series Sketch is a reconfiguration and an iteration. His “quasi self-portraits,” as he defines them, may be the voice where Wilson’s eyes are the eyes of others, shaped by the people he has spent time with and met on his journeys. Felicia (2016) simultaneously opens to a multiplicity of subjectivities that fills up her sight. James says that, above all, he wants to tell the truth of the dispossessed youth—from “a one on one point of view perspective.” The eyes that compose Wilson’s works are inside, looking through the subject.

Felicia (2016) by J. Wilson. Acrylic on Canvas, 36 x 24in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

The thoughts and experiences shared by Wilson recall Simulacra and Simulation[4] by Jean Baudrillard, who introduces a different way of understanding our relation to the city. Baudrillard identified the end of panoptic and perspectival space.[5] In Newark, we can find parts of the panoptic city. The latest Prudential Financial Center developments reverberate as “one in a chain of panoptic structures with a constant gaze throughout Newark’s core.”[6] Yet Newark also represents a perspective, as will be seen through the work of Manuel Acevedo.[7] James Wilson may point to both the end of panoptic and perspectival space in Newark. He has identified a saturation of sociality, meaning many priorities where, in fact, local urban community falls in as if under the weight of excessive, external intentions. This means that politics, that is, politics based on representation and vote of community, is dead. In that sense, not only is the concept of a city dead, but power is dead. Wilson noted that politics is empty if based on pockets of interests and agendas that lack sincerity and compassion.

Rising Down (2016) by J. Wilson. Acrylic on Canvas, 36 x 48in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Pier Paolo Pasolini says there is nothing more anarchic than power—it does what it wants while going beyond any logic.[8] The borders drawn by finance, as referenced by James, dissolve their own limits while creating limits to others. This is something imposed on society, as in a consumption, which is what Marx, as cited by Pasolini, had called the “genocide of living cultures.”[9] At the same time, for Baudrillard, “criticism and negativity alone still secrete a phantom of the reality of power”—some people seem to fight against the power but in reality they keep it alive as a hallucination.[10] This appears to be something the Artist knows well, considering Wilson is an observer of what happens. He can be present without feeding the phantom. Signs, as Baudrillard also observed, were for him the real resemblance of power—the more power disappears, the more its survival increases.[11] There will be no perspective, no panopticon, but total power everywhere, in the absence of any power.

James offers total power transparency—total power as paved by both the anarchy of power, like in the thought of Pasolini, and the absence of power, of Baudrillard. Transparency, because when it comes to the presence of the total, the Artist does not give it any more attention than it needs.

Subway Series (collaged) (2012–2014) by J. Wilson. Pencil on Paper, 11 x 20in. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Like Felicia (2016) and GCM 2 Series Sketch (2015), Wilson’s Subway Series (2012−2014) is an observational drawing project about life on the PATH train between Newark and New York City. The Series comes from a place where perspective is dissolved. He sketched from inside the daily commuter train that is similar to the restricted mobility of the commuter tunnel. Once again, this is how James dealt with design imposed on society. Most of Wilson’s subjects were unaware they were being drawn—except for the rare occasion when Wilson was caught by his subject. He kept hiding and playing from inside—with being seen or unseen, just as he had moved with freedom growing up in Newark.

Wilson rapidly sketched commuters as they all moved in and out of Newark. He completed each drawing and documented the time. The many people on his route eventually dissolved at every transit point. Rather than being absorbed by the commute, Wilson kept himself sharp. He is able to deal with what we are taught to do or told to watch because he represents an intimate part of people that are unaware of what they show.

Through his art, James Wilson offers a “sense that no one is alone.” He is an artist who works from inside because it is his duty and his art has a purpose. James brings meaning to a medium that might otherwise be lost.

SB: How would you define “dispossessed?” Based on how Newark has changed, and where it is going.

JW: How do I describe the dispossessed? It’s simple—look at myself born of circumstance in some of the most volatile conditions. Yet life finds a way. Until this day, I’m not hesitant to admit that due to extenuating circumstances, I may still feel inherently inferior or possibly lacking when it concerns certain situations. Of course, we adapt, grow, and learn. But why is it that I may feel this way at times? All because of society’s constraints and/or norms, put forth upon me no matter how minute, no matter how trivial. For example, as I began to settle into some work situations over the years, I had noticed people—maybe not refuse but rather avoid, or be a little bit unsettled, when speaking with me unless invoked. So what does that mean? It’s probably nothing. However, when I bring up the matter with my supervisor, just on a whim to simply state my observation, its blown off as if it were nothing. I know it might sound trite to say the least, yet it bothers me. This sort of nonsense happens all the time and is just something we have to live with. There were times in my own gallery studio setting where I felt completely alienated and alone even as I passed by a large group in the hall on my way up to my studio. I tend to have to go out of my way when speaking to strangers who may be a little apprehensive. Yet on another note, a great example for the opposite is the overly familiar approach: I call it the “yo!, yo!, yo!” quote. This is when someone decides you’re from the streets, hood, or what have you, making the assumption that this is how I speak or that they know my locale for that matter. While working in Manhattan as a freelance art handler, this was known to occur in many a random situation over the years. What’s politics for a young skateboarder who wanted to go skateboarding with some friends in the neighboring town of Kearny, but made a simple mistake? One that would not reoccur, since I learned to avoid detection by being alone or taking the bus. However, on this occasion he decided to roll with some of his fellow friends from the neighborhood. When just after we crossed the Clay Street Bridge we were promptly stopped by the police and told to turn around and go back to Newark “where we belong”… home sweet home. How ‘bout being 12 years old trying to play army in Branch Brook Park and having the police stop you and tell you to get face down on the ground while holding a gun point blank in ya face as they looked for a quote unquote rapist in the area. What’s politics when you’re the periodical son of your hometown, and yet, forgotten by your peers, where the “posers” quote unquote “Newark-based” artists, rather than Newark born and raised, are allowed leverage, seems absurd. Of course, we all gotta eat. Like I said I don’t really do politics. Rather like, most have been done over by them. Ha.

SB: What is politics, and what is politics in Newark?

JW: Politics for me has always been a matter of opinion, so I usually don’t talk politics. But when it comes to Newark politics, I think it mainly comes down to different agendas, and/or priorities from different factions or groups. Sometimes people have their hearts in it (City), and others maybe not so much. It feels more like ego or simply a meal ticket… I digress.

I think maybe at its core, politics requires true sincerity and compassion for your counterparts.

SB: Would you say there are no more politics? Rather, agendas as politics?

JW: As I stated prior, politics tend to turn me off. Not so much because I don’t care. I’d rather not care because when I care, I tend to care too much. My passion as an artist tends to take over and leads one to lose better judgment. Emotion is the crutch of many a drastic decision, as I’d like to say. That being said, I’d like to acknowledge our current state of affairs where our civil/human rights are being dissolved before our eyes while we stand idly by, simply mesmerized and marginalized as a people, let alone a nation, quote unquote “indivisible”. The term politics, Poly, meaning many, and tic’s meaning blood sucker’s—has never felt more suiting. Agendas are like opinions. We all got one, and they are the inexplicable result of humanity’s frail attempt to will the world to its desire. All the while leaving misery and destruction in its wake and all in the name of uplifting the people. That is “Democracy,” similar to the great conquest and colonialism from which I am an end result. Here too, I echo through the ages of time for my ancestors who cannot speak for themselves. Much as my counterparts, lost in the tombs pre-destined for the hell pits of society where being jailed and institutionalized has become a “rite of passage” of sorts. When all your role models have had to bear the cross of the civilized world in order to survive or persist, simply because of bad politics. Of course we all have agendas, do we not?

SB: How do you see Newark in 20 years?

JW: I believe Newark will be alive and well in 20 years. It will definitely be different, hopefully for the better. Lots of cities are inhaling—versus exhaling, as they did in the past. I think some people are realizing that maybe suburbia is not always an ideal setting. Even I want to be able to live, work, and play all in one general place.

SB: Do you think Newark has been a suburb? Or, is suburbia coming to Newark?

JW: If Newark is a suburb? No more than Manhattan is a suburb or Brooklyn, New York. Newark has never been a suburb in my eyes but more of a purgatory, where worlds collide. Newark is a city like any other. We have in Newark, highly developed city street areas such as the business district. Meanwhile, we have highly idyllic residential areas between which you may move freely, of course. Similar to all major cities throughout this nation, we are divided by race and economics, historically defined. Yet invisible lines exist to this day. All of which we still follow or adhere to inherently, simply because. Is suburbia coming to Newark? I’d like to think not. With deep consideration, I do understand the appeal for the “upwardly mobile” to feel the need to venture into our fair city. Nonetheless, Newark does have more advantageous places to live. I realize there is plenty city for all of us, as long as we all can get in where we fit in. I think that’s what makes Newark a great sheer diversity.

SB: Can you speak about your art and your relation to Newark?

JW: Well, I think it’s safe to say that without Newark there would be no “My Art.” It’s my hope that my art can speak for Newark’s unspoken. While in a broader sense, it speaks for the signs of the times. That’s my duty as an artist—for my work to be a window back in time, snapshots of sorts, and hopefully providing insight, pushing progress forward…

SB: What about your Subway Series, and the people who live and pass through Newark?

JW: The Subway Series was a personal challenge I set for myself. As artists, we have to stay busy and explore thoughts and ideas. In the case of the Subway Series, I documented not only the people in the drawings, but I documented myself, plus my travels to and from Newark. During those days, late 2011, I was an art handler at either Chelsea or Sotheby’s.

SB: How would you build a post-industrial city? How do you see community in a post-industrial city?

JW: Hmm, that’s a tough one. I’m the guy that has the great ideas but doesn’t quite, really wanna be in charge, but then will step up to the plate when the situation calls for it. I have no idea how to run a city. I do know how I may like things to be better. How do we as a society not have economic status define our quality of life?

All my life, I’ve watched new borders being drawn or pushed back simply due to finance. From location to education, to what one may consider acceptable—as to what is not—it’s all merely a matter of location in the city or suburbs. Cities should be quality of life incubators for all their citizens, to be able to live, work, and play—all while living fulfilling lives rather than just dredging through life check to check with very little substance for one to feel whole or complete. The term “community” for me seems like such a vague fallacy sometimes. We tend to sell the word as this sort of all-encompassing easy go-to: “Oh my community this, my community that.” When was the last time we really interacted with our community? What community? When you’re from a city, born and raised, where there’s always an air of “looming danger,” you tend to be a ‘lil more jaded, as in a little less likely to want to just spark random convo in the streets with a stranger. Go figure.

Aside from your immediate neighborhood, and a few odd neighbors there’s minimal interaction. I’ve lived next door to people for years and have never even known their name, let alone care. For the most part, what becomes your “community” tends to be people you see more often, work friends—art or shared interest friends, and associates as in skateboarding, art, music, et cetera. These are the folks whose names I actually remember. I see them regularly over the years, building relationships over time, as a community should be.

SB: Today, according to you, what is a good city? How does this relate to Newark—not only today, but yesterday and tomorrow?

JW: Today, for me, the best a city can do for one, as an artist, is to have a place where I can make moves and to live, work, play, and progress as an artist. Lately I have felt slightly stagnated and disenfranchised in a way, especially when it relates to the “Newark Art Scene” that is today. As for the future, only time will tell. Yesterday may have been better economically, however. Newark needs what is happening. Nonetheless, gentrification is a bitch and we are all screwed in that sense. “Without the night, can’t arrive the sweet dawn,” as Lauren Hill said. Change sucks sometimes, but it’s still a good thing.

SB: Is your art related to the concept of city? If so, how?

JW: My work? Well, lately I’ve been using my quote: “I’m Graffiti Meets Fine Art.” When worlds collide, so to speak. Being born and raised in the city, it’s only natural that my work reflects that. But in a broader sense, my intention is to represent the human condition in all its facets.

SB: Can you critique, from your point of view, the calculated design additions in Newark, that in reality, bring a subtraction of Newark?

JW: From “my point of view” is interesting use of wording. I technically have been privileged enough to remember the Gateway Center being built as an example of eliminating social interaction between the corporate offices located there, and the everyday foot traffic that one may find on the ground level of Newark, New Jersey’s streets in the late 80s, early 90s. All of the buildings in the Center are connected via different, above street level walkways or corridors. Providing employees complete access to parking and transportation (via Newark Penn Station), and eliminating any need to ever set foot on the ground of Newark. One is able to completely avoid all the elements, whether person or nature. Some examples also include institutions that set forth with the best of good intentions initially, but for lack of a better term, tend to become these sort of parasitic art entities feeding off of the artist as a means to suit their own artistic ventures—hence neglecting the whole “community” they claimed to serve. Of course as an artist, we all gotta eat, huh?

SB: Can you talk about skateboarding in Newark? What is the relation between your body and the body of Newark?

JW: I’ve been skating here in Newark since before it was “cute”—as I like to say. By saying that, I mean it wasn’t the most popular thing to do when I was 10 years old and growing up here in Newark. Which is what made me gravitate toward it more. I was always the oddball in the neighborhood, so it seemed fitting. To this day, my old neighborhood where I grew up, the “Garden Spires” just off of 1st and Orange Streets, calls me “Rambo” because I made weapons like bows & arrows, et cetera, and loved to play “army” or “Shadow”—as I would grow to call it—since the point of the game was to be a ninja of sorts hiding out and avoiding detection from those in your immediate surroundings. The “Spires” are known to be a sort of “rough” neighborhood at times, although when it’s your hood then you’ve never felt more at home. I think that me playing army and making weapons was my kind of coping mechanism. It afforded me the opportunity to move freely amongst my peers even if they weren’t quite on my page.

SB: How do you support the freedom of your art?

JW: Sheer will and determination… I support my art by being me and maintaining a good practice, however, minute it may be at times. I support my work through various means, some being more predominant than others such as art handling and teaching art workshops… creating murals, prints, and of course painting—which is the end goal is it not? The creation of objects of beauty…

James (J.) Wilson, Scorebrx, as a “Graffiti Meets Fine Art” artist, curated “Graffiti, The Art of Getting Up” (2015) at City Without Walls, Newark, New Jersey.

Wilson’s Subway Series—Artistry in Motion was featured in “Subway Series 2012–Present” at Paul Robeson Galleries, Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts at Rutgers (2015).

James has been a City Without Walls mentor through its ArtReach XXV + Newark New Media programming and exhibitions, which puts local high school art students in contact with working artists.

The work of James Wilson (Rising Down, 2012) is part of the Newark Special Collections Division at the Newark Public Library. In addition to painting and drawing, Wilson’s practice includes murals, three-dimensional works, and tattoo art. Wilson can be found at Scorebrx.

Footnotes:

[1] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015), 13−15.

[2] Melgar, C. (2016). Newark [All Issue Photography]. Journal of Biourbanism, IV(1&2/2015).

[3] Located in the Central Ward at 195 1st Street, Newark, NJ. As of July 2017, the City of Newark (Administration of Mayor Ras Baraka) has since filed a lawsuit (July 14 in Essex County Superior Court) against property owner First King Properties, LLC (Kearny, NJ) due to poor management. Of the 550 units, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) subsidizes 350. See: Yi, K. (2017, July 18). In city-wide crackdown, Newark sues landlord over rodent-infested apartments. NJ.com: New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved August 5, 2017 from http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2017/07/newark_sues_garden_spires_landlord_over_uninhabita.html

[4] Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. (S. Faria Glaser, Trans.). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. (Original work published Simulacres et simulation 1981)

[5] Ibidem, The precession of simulacra: The end of the panopticon, pp. 27−32.

[6] Melgar, C. (2017, February 20). Cesar Melgar—“Razing history to make surface lots is a famous Newark administration pastime.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism. Retrieved from https://www.biourbanism.org/cesar-melgar-razing-history-make-surface-lots-famous-newark-administration-pastime/

[7] Acevedo, M. (in press). Manuel Acevedo—“In Newark, I can imagine a new building but in decay. The way I see it, the completion is relative.” (Interview by S. Bissen). International Society of Biourbanism.

[8] Bachmann, G. (1975–1976, Winter). Pasolini on de Sade: An interview during the filming of “The 120 Days of Sodom”. Film Quarterly, 29(2). doi:10.2307/1211747 In Bertolucci, G. (Director). (2006). Pasolini prossimo nostro [Interview footage from Documentary]. Italy: Cinemazero.

In reference to the interview, Pasolini says: “Nulla è più anarchico del potere. Il potere fa praticamente ciò che vuole, e ciò che il potere vuole è completamente arbitrario, o dettatogli da sue necessità di carattere economico che sfuggono alla logica comune.”

See also:

Pasolini, P. P. (2016, September 20). Il vuoto del potere. [The vacuum of power]. (R. Perez-Chaves, Amended English Trans.). Retrieved August 5, 2017 from http://cittapasolini.blogspot.it/2016/09/the-vacuum-of-power-il-vuoto-del-potere.html (Original work published 1975)

Pasolini, P. P. (1975, February 1). Il vuoto di potere in Italia [The void of power in Italy]. Il Corriere della Sera. Subsequently re-titled: L’articolo delle lucciole [The article of the fireflies] and included in the volume Scritti Corsari [Corsair Writings]. Milano: Garzanti. pp. 128−134.

[9] Pasolini, 1975.

[10] Baudrillard, J. (1994). The precession of simulacra. In (S. Faria Glaser, Trans.). Simulacra and simulation (p. 24). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. (Original work published Simulacres et simulation 1981)

[11] Ibidem, p. 23.

For further study, see: Newark—on Heterogenesis of Urban Decay